ALBANY, Jan. 26, 2021 — For nearly a decade, the Cuomo Administration has narrowly applied state environmental law to a pair of Finger Lakes industrial projects in ways that favor their out-of-state owners at the expense of those most likely to be harmed.

In response, broad, science-based coalitions of nearby residents, businesses and municipalities have called on Gov. Andrew Cuomo to revoke or deny permits for Atlas Holdings’ Greenidge Generation power plant on Seneca Lake and Cargill’s immense salt mine beneath Cayuga Lake.

The latest spur to public alarm is Greenidge’s plan to expand its Bitcoin mining operation in Dresden, powered by unregulated, off-grid electricity it generates.

“It is reckless to allow a 70-year-old fossil fuel-burning facility (Greenidge) to power a Bitcoin mining operation,” the Committee to Preserve the Finger Lakes said in a Jan. 25 letter to Cuomo signed by more than 100 businesses, including wineries, breweries and tourist firms. Another CPFL letter Cuomo has more than 600 individual signatures. (Greenidge issued a statement Jan. 27, saying CPFL’s letters to politicians were “more about creating headlines” than a better environment.)

The letters, like a proposed resolution set to be considered by the Geneva City Council Feb. 3, claim the Bitcoin project offers no public benefit while threatening to boost greenhouse gases, harmful algal blooms and noise, while also wrecking a trout habitat.

The outcry over the Dresden plant follows years of public angst over Cargill’s salt mine, which inspired a 2017 letter to Cuomo that has attracted 1,144 signatories over three years. It urges the governor to block all state permits allowing mining under Cayuga Lake, saying:

“We underscore that your administration bears sole responsibility for … granting mineral rights underneath Cayuga Lake.”

The grass roots movements are reminiscent of public groundswells that prodded Cuomo to ban fracking statewide in 2014 and to block construction of a Finger Lakes garbage incinerator in 2018.

Throughout the governor’s 10 years in office, state regulators have repeatedly deferred to Atlas Holdings, Cargill and the law and lobbying firm that represents both, Barclay Damon.

The Administration has adopted the companies’ legal rationales for denying the public the most potent tool state law provides for protection against harmful or dangerous projects: the environmental impact statement, or EIS.

State law requires any developer to prepare an EIS — as part of a comprehensive risk assessment process with public hearings — if a project “may include the potential for at least one significant environmental impact.”

Cuomo’s regulators have declined to enforce that basic requirement at the Dresden power plant or the Lansing salt mine. Instead, they have summarily ruled that key developments at each site “will not have a significant adverse environmental impact.”

But Cargill’s mining of salt deposits beneath thin or irregular bedrock risks a mine flood or a catastrophic mine collapse, according to independent scientists and the chair of the state Assembly’s Environmental Committee, a geologist.

They have noted strong geologic similarities to the immense Retsof salt mine in Livingston County, which collapsed in 1994. And they were further unnerved when two miners were killed in mid-December after a roof collapsed at Cargill’s salt mine in Louisiana. That mine still hasn’t resumed normal operations, a company spokesman Friday.

Despite the potential for a Cayuga Lake mining catastrophe that could run into the billions of dollars, Cuomo is the latest of five New York governors to allow Cargill to sidestep an EIS for its 13,000 acres of mining reserves under the lake.

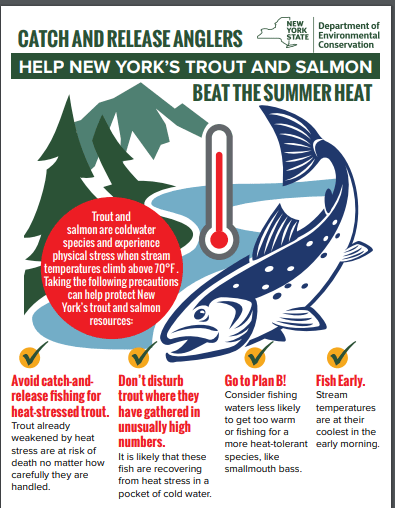

Meanwhile, Greenidge is permitted to discharge up to 139 million of gallons of heated water a day into Keuka Outlet, a designated trout stream that flows into Seneca Lake. While trout suffer at water temperatures above 70 degrees, Greenidge’s DEC permit allows for discharges up to 108 degrees.

Atlas Holdings has also managed to dodge an EIS, even as it prepares to dramatically boost electric generation — and the volume of lake water needed to cool its generating equipment — to process Bitcoin transactions.

Industrial developers often strive to avoid the EIS process because it is costly and time-consuming. It can also shine a light on inconvenient facts that make it harder to win a permit or that fuel public opposition.

EIS waivers may be granted either by local officials or the state Department of Environmental Conservation. Normally, the DEC makes the call when entire regions may be exposed to environmental risk.

But when the Planning Board for the Town of Torrey, population 1,241, waived an EIS for the Bitcoin project late last year, the DEC stayed on the sidelines.

That decision was the latest in a string of friendly actions Cuomo Administration officials have bestowed on Atlas, a private equity firm based in Greenwich, Conn. It manages 250 facilities worldwide, generating $11 billion in annual revenues. The company and its top managers have contributed at least $120,000 to various Cuomo campaigns.

Greenidge was built in the 1930s to burn coal, which it did until a bankrupt previous owner shut it down in 2011 with plans to scrap and demolish it. But Atlas stepped in to buy the plant in early 2014.

The Cuomo Administration gave Atlas’ restart plans a big boost by awarding it a $2 million state grant on the notion that it would create needed jobs in Yates County.

Greenidge has continued to promote its role as a jobs-creator. Last October, plant manager Dale Irwin told Torrey officials that full-time, skilled jobs at Greenidge had risen steadily from five in 2015 to 27 last year.

The DEC granted Atlas its restart permit after ruling in 2016 that no EIS would be needed. The agency’s environmental analysis that led to the EIS waiver excluded the plant’s coal ash landfill, Lockwood.

In Feb. 2015, the agency and the company had entered a consent agreement that called for a cleanup of Lockwood’s toxic leachate discharges by October 2016. The DEC later allowed multiple deadline extensions for that cleanup.

The agency also allowed the company five years — until 2022 — to install federally mandated screens on its Seneca Lake intake pipe. Further, DEC did not require installation of a closed-cycle cooling system, which could reduce hot water discharges by 95 percent or more. A 2011 DEC policy memo had recommended closed-cycle cooling for new and restarted plants.

The hot water flow into the lake increases the likelihood of toxic algae blooms, or cyanobacteria, in the Dresden bay area, according to a sworn affidavit from Gregory Boyer, a biochemist and algal bloom specialist at SUNY-ESF.

“(Greenidge) discharges are likely to result in increases in the water temperature of the Dresden bay area of Seneca Lake,” Boyer wrote. “Increasing water temperatures … could result in increased HABs outbreaks in the area.”

Several high-toxin blooms were reported in shore areas around the plant in 2016 through 2019, though none were reported last summer. (In 2019 the DEC halted its financial support for testing the toxicity of blooms.)

Before restarting, Greenidge also need clearance from the the Cuomo Administration’s Public Service Commission, which regulates electric utilities.

The PSC had to weigh whether to grant Greenidge a Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity over the objections of dozens who argued that electricity from the plant was not needed to meet regional energy needs.

Light demand notwithstanding, the PSC granted that crucial regulatory approval in late 2016. It said it had concluded that the plant would operate “exclusively on a merchant basis in the competitive wholesale power markets” — that is, selling power to the grid.

Greenidge restarted in March 2017 after six years of dormancy. It soon discovered slack demand for its energy. For two years, it operated only sporadically, far below its 106 megawatt capacity.

Atlas’ resourceful response to the weak energy market was energy-intense Bitcoin mining.

In early 2019, Atlas announced that it had launched a cryptocurrency mining operation in Dresden, using banks of computers powered by Greenidge-generated electricity to process Bitcoin transactions.

The juice used to power the processors never reaches the electric grid. The trade press applauded Atlas’ innovative use of “behind-the-meter” power.

Neither DEC nor the PSC raised objections. Then, last June, the PSC ruled that the off-grid energy use was not subject to its regulation, regardless of potential environmental issues.

Also that month, Greenidge applied to the Torrey Planning Board to dramatically increase its Bitcoin operation. That triggered a lawsuit by the Sierra Club, CPFL and Seneca Lake Guardian against Greenidge and the Planning Board, asking a Yates County court to compel an EIS.

At least a dozen Barclay Damon lawyers have had a hand in litigation or in otherwise laying the groundwork for Atlas’ run of regulatory wins.

The Syracuse-based firm has more than 270 attorneys. Its partners include state Assembly Minority Leader William Barclay (R-Pulaski), Sen. Tom O’Mara (R-Big Flats), a former chair of the state Senate Environmental Conservation Committee, and Frank Bifera, a former DEC general counsel.

The Greenidge plant is in O’Mara’s Senate district and the Cargill Salt Mine sits on its border with the district represented by Sen. Pam Helming (R-Canandaigua). Both senators have opposed recent environmental legislation, including Cuomo’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.

In addition, O’Mara sat in on a key Albany meeting on Greenidge in 2015 with a top Cuomo aide, the DEC Commissioner, the agency’s top lawyer, Atlas’ co-managing partner, Atlas’ top lobbyist and Bifera. At the time, O’Mara had recently been appointed chair of the Senate’s environment committee.

Barclay Damon joined the Cargill team in November 2017 when it acquired a smaller Syracuse law firm that had long handled Cargill’s New York regulatory matters.

At the time, Cargill was facing mounting public and legal challenges to its planned construction of a new air shaft designed to address federal mine safety requirements at its Cayuga Lake salt mine.

Minnesota-based Cargill is the nation’s second largest private company (Koch Industries just passed it last year). The international agribusiness has annual revenues of $115 billion — roughly the same as Microsoft or Bank of America.

Heirs to the 155-year-old family business, who own 88 percent of the company, include eight billionaires. They collect a portion of it profits as dividends, according to Forbes.

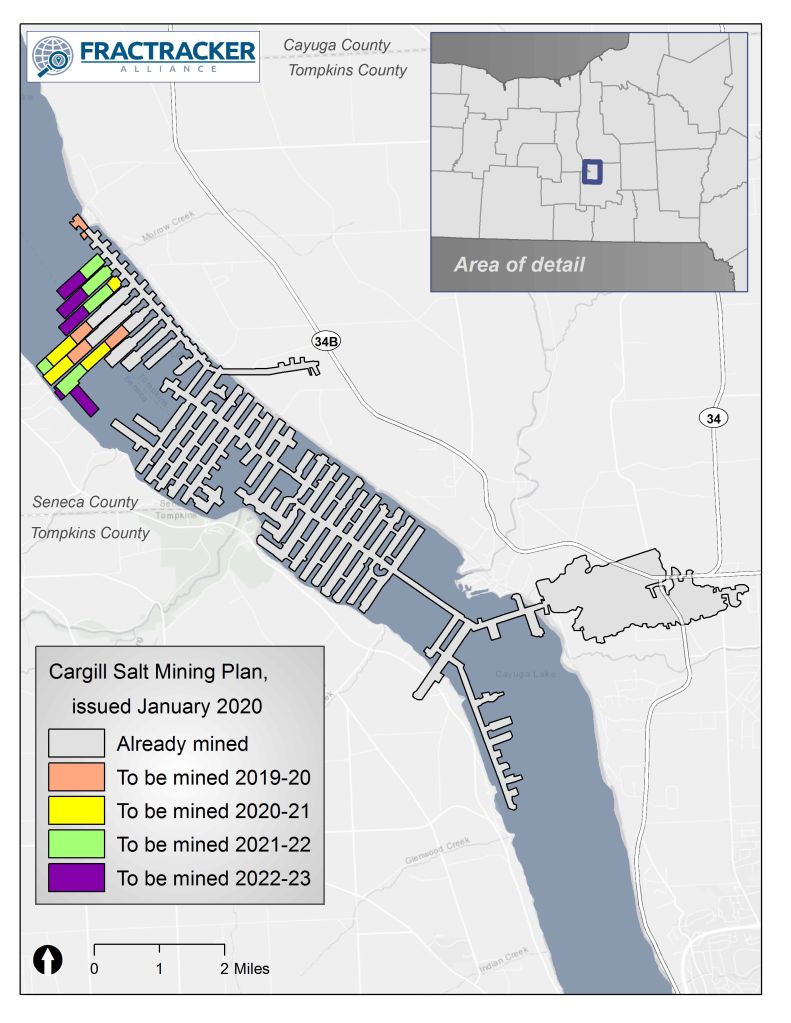

Cargill bought the Cayuga mine in 1970. Today its mining reserves cover more than 13,000 leased acres — about one-fifth of the state-owned land under the lake.

Miners work 2,200 feet below ground to extract rock salt used to de-ice winter roads. New York consistently leads the nation in the use of salt on its winter highways, and the company has state salt contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

For years, Cargill’s miners have been working their way northward under the lake, pushing toward areas where the bedrock separating the lake from the mine tends to be less consistent.

In 2003 the state added more than 5,000 acres to Cargill’s “northern reserves.” The administration of Gov. George Pataki did not require an EIS that would have allowed members of the public to peek at the geology in the reserves and draw their own conclusions about potential risk.

A year earlier Ithaca geologist William Hecht filed a Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request for detailed seismic and geological data on the mine. Months later, the DEC’s chief administrative law judge recommended granting much of what Hecht had requested.

But Cargill continued to dispute the request, claiming certain documents were “trade secrets.” Hecht eventually lost a three-year FOIL battle in 2005 when an assistant DEC commissioner overruled the chief ALJ.

The group CLEAN (Cayuga Lake Environmental Action Now) and others have complained about lack of data transparency ever since.

Their concerns peaked in 2017 when the DEC granted Cargill a permit to construct a ventilation shaft on Ridge Road in Lansing — again without an EIS.

The new shaft was seen by many as critically important for mining the northern reserves. Federal rules require that miners be able to evacuate within one hour. Without the new shaft, miners wouldn’t have time to escape certain northern sections through existing shafts.

CLEAN and the municipalities of Ithaca, Ulysses, Union Springs and others, including Hecht, later sued Cargill and the DEC for not requiring an EIS. They also alleged the agency had illegally segmented its environmental analysis of the shaft project.

The shaft site, acquired in 2012, was more than a mile away from the salt mine, so Cargill needed a way to connect them. It sought a permit to mine a narrow, mile-long strip of 150 acres from the mine to the acquired property.

The DEC granted a permit to mine the strip in 2015 — without an EIS — after it had inaccurately advertised the project in the agency’s public notice bulletin, stating: “There will be no surface development associated with this proposal.”

Days after the statute of limitations on potential challenges to the 150-acre project ran out, Cargill applied for a permit for the shaft, claiming it was for egress and ventilation, unrelated to mining.

State law discourages the segmentation of environmental analyses but does not flatly ban it in all circumstances.

Steve Englebright (D-Setauket), the geologist who chairs of the state Assembly’s Environmental Conservation Committee, wrote DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos 2017 to express his and others’ qualms about the mine shaft project. Barbara Lifton, a former Assembly member representing Ithaca, co-signed the letter.

Englebright referred to the 1994 disaster at Restof — once the largest salt mine in North America — that led to “massive sink holes” and property damage. Citing the warnings of SUNY Geneseo geologist Richard Young, he urged the DEC to “avoid approving activities which will, directly or indirectly lead to salt mining under Cayuga Lake.”

Aside from Young, geologists John K. Warren and Raymond Vaughan had also argued that sub-Cayuga mining was high risk.

Englebright noted that “lateral compressive tectonic forces are most severe” under the lake, and recommended that Cargill’s future mining should be under dry ground.

Walter Hang, a long-time environmental activist who runs Toxics Targeting in Ithaca, drafted the 2017 letter to Cuomo that has been signed by more than 1,100 people.

Hang wrote that the shaft permit decision was a “once-in-a-generation opportunity to safeguard Cayuga Lake from potential mining disaster.” Denying the permit would allow mining under the lake to be phased out, he added.

In response to Englebright, DEC Commissioner Basil Seggos wrote that the new shaft “does not immediately impact the mine or mining operations.” Seggos said that activity was already permitted “and may continue with or without the (shaft) construction.”

DEC granted the shaft permit in August 2017, triggering the lawsuit from CLEAN and the municipalities. Cargill and the DEC later won that lawsuit as well as an initial appeal. The matter is under further appeal.

In April 2019, the DEC renewed Cargill’s mining permit. Last summer, the agency proposed changes to that permit to prohibit mining in specific geologic “anomalies” — weak rock formations that may put the structural integrity of the mine at risk.

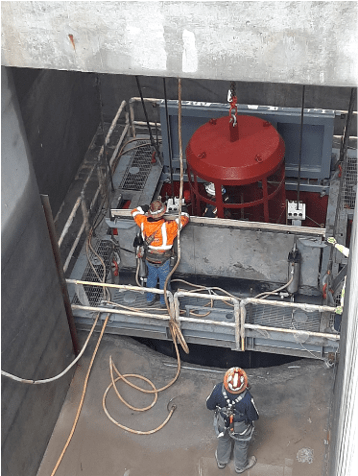

Cargill has provided excellent detail on the progress of the shaft construction.

Cuomo’s press office referred questions to the DEC, which responded late Tuesday:

“DEC strictly oversees Greenidge Generation’s operations and its compliance with requirements to protect public health and the environment. This facility is currently operating in compliance with its DEC permits and there is no basis at this time to modify or rescind Greenidge’s permits. This facility’s current Title V air permit will expire in September 2021, and if Greenidge submits a renewal application, DEC will evaluate whether the renewal would be consistent with New York’s Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.

” To help mitigate potential impacts to fisheries and water quality, DEC is reviewing a Thermal Study Criteria Workplan and will oversee the installation of an intake screen.”

With respect to Cargill’s salt mine, the DEC said: “DEC subjects all permit applications to rigorous review to protect public health and the environment and will continue its strict oversight of this facility. After a comprehensive review and public input, DEC issued the permit for the Shaft #4 Permit in August 2017. DEC regularly inspects the Cargill Mine for compliance with the state Environmental Conservation Law and regulations.”

For the complete DEC response to WaterFront questions, see here.

Wow. That should piss him off.

Mary Anne Kowalski. 315-759-3761

On Tue, Jan 26, 2021, 6:36 PM Water Front- Peter Mantius wrote:

> Peter Mantius posted: ” ALBANY, Jan. 26, 2021 — For a decade, the Cuomo > Administration has narrowly applied state environmental law to a pair of > Finger Lakes industrial projects in ways that favor their out-of-state > owners at the expense of those most likely to be harmed. Th” >

LikeLike

“State law requires any developer to prepare an EIS — as part of a comprehensive risk assessment process with public hearings — if a project “may include the potential for at least one significant environmental impact.”

“Cuomo’s regulators have declined to enforce that basic requirement at the Dresden power plant or the Lansing salt mine. Instead, they have summarily ruled that key developments at each site “will not have a significant adverse environmental impact.” ”

As a member of a local planning board, I cannot believe that the state agency responsible for the environment can be allowed to make a negative declaration without an EIS on a project like this.

LikeLike