DRESDEN, Nov. 13, 2020— A local fisherman is urging Torrey town officials to consider the declining state of Seneca Lake’s fish before they approve Greenidge Generation’s planned expansion of its Bitcoin mining data center.

“The fishing’s gone to hell,” and the Dresden power plant might be one reason why, Michael Black, owner of a lake cottage in Dundee, told the Torrey Town Board Tuesday night.

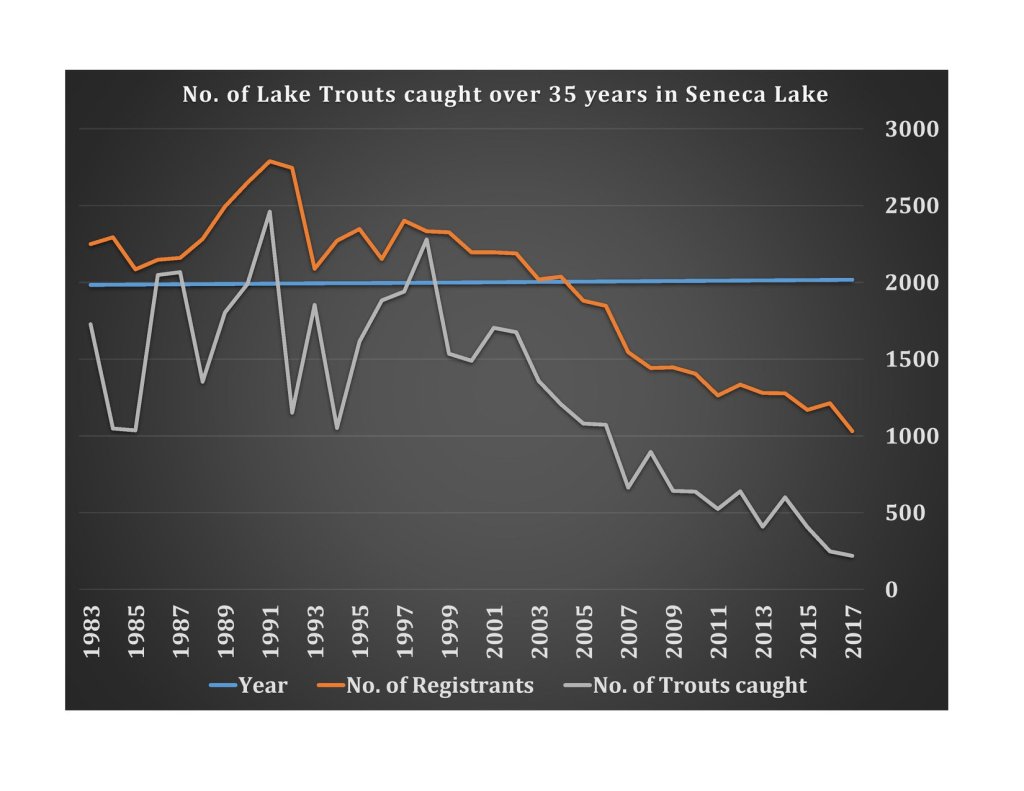

Black, who’s fished the lake steadily since the 1970s, said he’d routinely catch 35-50 fish during the National Lake Trout Derby on a Memorial Day weekend, sometimes winning prizes. “For the last five years, I’m lucky if I’ve caught one fish for 200 hours of fishing….I know a lot of fishermen who are going to Cayuga, to Keuka, to Lake Ontario and they’re skipping right by Seneca.”

But when Black hinted that the Greenidge plant — along with salt plants and other industries on the lake — may have contributed to the fish die-off, the plant’s manager heatedly sprang to its defense.

“Before you point fingers at Greenidge, I wish you’d … get the facts right,” Dale Irwin said as members of the Torrey Town Board silently looked on.

Irwin acknowledged that Seneca Lake’s “fishing has been going down since the early 2000s. It is getting harder and harder to catch the fish.”

But Black’s reported lack of success over the past five years doesn’t fit the Greenidge timeline, Irwin said. That’s why blaming the power plant, built in the 1930s and restarted in 2017 after a six-year shutdown, irresponsibly risks “putting 30 people out of jobs,” he said.

Black said Greenidge’s effect on Seneca fish was likely cumulative over decades. He said Greenidge needs to make sure its planned expansion doesn’t further raise lake water temperatures or suck up even more fish in its inefficient once-through cooling system.

“I’m not trying to put anyone out of jobs,” Black said. “I’m not saying you can’t run your business. I’m saying you need to be responsible for the lake and not take advantage of the lake.”

Many of the 400-odd formal comments Torrey officials have recently received related to Greenidge’s proposed expansion cite the project’s likely negative effects on fish.

Some that have been made public call for local officials and/or the state Department of Environmental Conservation to require Greenidge to prepare an environmental impact statement — a step that both the company and the DEC have vigorously resisted.

“With little or no scrutiny, the DEC simply grandfathered the old discharge permit limits and allowed extensive time for studies to design and implement the necessary actions to reduce fish kills, including thermal studies and screens to protect fish from the intakes, and to set pollution discharge limits,” the Committee to Preserve the Finger Lakes (CPFL) wrote in a recent email to Torrey officials.

can kill trout, but it allows Greenidge to discharge

millions of gallons of much warmer water into

Keuka Outlet, a designated trout stream.

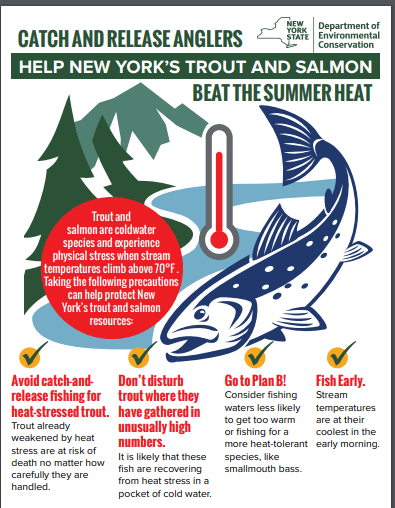

Those permits allow Greenidge to discharge 134 million of gallons of hot water (up to 108F degrees) a day into Keuka Outlet, a designated trout stream, even though the DEC warns anglers that water temperatures above 70F stress or kill the heat-sensitive fish.

The DEC allowed the plant to restart in 2017 on the condition that it would within five years install screens on its huge water intake pipe to minimize harm to fish and other aquatic species. The federal Clean Water Act requires such screens, and virtually all U.S. power plants have them. Greenidge doesn’t (and won’t until 2022, at the earliest), thanks to the DEC’s forbearance.

The DEC issued the permits to allow Greenidge to supply energy from its natural gas-powered generators to the state’s electric grid. But as that business has floundered, the plant’s owner — Atlas Holdings, a Greenwich, Conn., private equity firm — turned to a new business model: Bitcoin mining.

Since early last year, Greenidge has been operating banks of computers to process Bitcoin transactions, powering them with energy that never reaches the grid.

This past June, the company applied to the Torrey Town Board for approval to expand the data center by adding four buildings (42×120 feet each) to house computer servers and noisy cooling fans.

In September, the Torrey Planning Board voted 4-1 to waive its authority to require an environmental impact statement for the proposed expansion.

CPFL has argued that the Planning Board’s decision ignored a Torrey zoning code requirement that approved developments must “not adversely impact … environmentally sensitive features,” specifically including Seneca Lake and Keuka Outlet. The dissenting voter, Ellen Campbell, agreed with CPFL.

In a Sept. 16 letter, CPFL president Mary Anne Kowalski asked the DEC to suspend, revise or revoke Greenidge’s four main air and water permits. The agency summarily declined to do so, stating in an Oct. 23 letter: “The facility is in compliance with the terms and conditions in all permits….We will not be suspending, modifying or revoking the Greenidge permits.”

Meanwhile, Greenidge told the Torrey Town Board on Oct. 13 that its positive relations with local governments had helped the company become “one of the world’s first fully-compliant cryptocurrency mining facility-power plant hybrid(s) that takes advantage of ‘behind-the-meter’ power generation to create maximum value for all its stakeholders.”

While the plant’s annual operating capacity dipped to 6 percent in 2019 when it ran only intermittently, the company has told potential investors that its goal is to operate full time and at full capacity (107 megawatts) to power the Bitcoin mining servers.

The company noted that its state permits are “based on the facility operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week.” And the DEC has ruled — in the face of significant evidence to the contrary — that such operation “does not have a significant impact on the environment.” That ruling has withstood several court challenges from the Sierra Club and others.

Furthermore, the company told Torrey officials, “this new project will not increase the water withdrawal or discharge from the plant into Seneca Lake” despite its planned dramatic increase in power generation.

Greenidge also noted that the DEC permits govern the generation — not the use — of electricity. “The use of that electricity is neither addressed in nor controlled by the DEC-issued permits,” the company said, opening the door for “behind-the-meter” (off-grid) operations.

If the company’s compliance with existing DEC permits isn’t in question, the adequacy of those permits is.

Discharges of heated water into Keuka Outlet, which flows in Seneca Lake, “will unquestionably alter the local ecology of the system,” Tiffany Garcia, a professor of Fisheries and Wildlife at the Oregon State University, wrote Torrey officials Nov. 7. “The totality of this effect … must be researched before the plant is allowed to operate,” Garcia wrote. “I implore you to consider science in your decision.”

CPFL, the Sierra Club, Seneca Lake Guardian and Seneca Lake Pure Waters Association have all argued that a long-sought environmental impact statement is needed now more than ever.

Across the lake in Waterloo, Seneca County Board of Supervisors weighed in with an Oct. 14 letter to the DEC that called for Greenidge’s operating permits to be rewritten or revoked.

“The decision to issue permits for the operation of this power plant, which no longer serves as a primary electrical power supply to the public power grid, is both illogical and inconsistent with the effort to preserve and protect the natural resources of the Finger Lakes,” said the letter signed by the county supervisor and the chairman of the board of supervisors.

Seneca Lake Pure Waters Association urged its members to write to Torrey officials, and it prepared a draft letter with suggested arguments. It focused on the DEC permit that allows Greenidge to discharge of up to 134 million gallons of water a day into the Keuka Outlet at temperatures recently measured at 90-100F degrees — well above the state limit of 70F for trout streams.

“The Keuka Outlet is a designated trout stream, and thermally polluted streams can see a decline in available oxygen, resulting in a decline in trout populations,” the SLPWA draft letter said.

DEC’s own website warns of the dangers of thermal pollution (but waives precautions in Greenidge’s case): “Trout and salmon are coldwater species and experience physical stress when stream temperatures climb above 70F degrees.”

Hot water discharges also tend to promote harmful algal blooms, Seneca Lake Guardian noted in its letter to Torrey. SUNY-ESF professor Gregory Boyer had warned of that link in a lawsuit affidavit. (While the Dresden Bay area had only one unofficial toxic bloom this year in a year that Seneca was largely spared, the area was a hot spot for toxic blooms between 2015 and 2019, and SLPWA officials expect future HABs outbreaks near Dresden).

The Sierra Club urged the Torrey Planning Board to reverse itself and require a full EIS in coordination with the DEC before the allowing the Bitcoin mining project to proceed.

“The potential for significant adverse impacts of these additional water withdrawals and heated water discharges on fish and aquatic life in Seneca Lake and on hazardous algae blooms should have been evaluated by the Planning Board … and they were not,” the group said in its Nov. 6 letter.

The Sierra Club has broad experience analyzing the cooling systems used by power plants across the country. In 2011, the group published a landmark study that was particularly critical of primitive “once-through” cooling systems like Greenidge’s. The study was called “Giant Fish Blenders: How Power Plants Kill Fish and Damage our Waterways.”

Antiquated “once-through” systems require between 14 and 50 times more coolant water than “closed-cycle” systems that recycle withdrawn water, the DEC reported in a 2011 policy statement memo. That document established “closed-cycle cooling as the performance goal for all new and repowered industrial facilities in New York” because they sharply reduce intake fish kills.

But the DEC hasn’t held Greenidge to that performance goal.

Atlas acquired the Dresden plant in 2014 — three years after a previous owner had sold the facility for scrap and sought bankruptcy protection. When Greenidge restarted the plant in 2017, the agency didn’t make installation of closed-cycle cooling a precondition of repowering.

Instead, it waived an environmental impact statement that might have led to public public pressure to install the more efficient and less deadly cooling system.

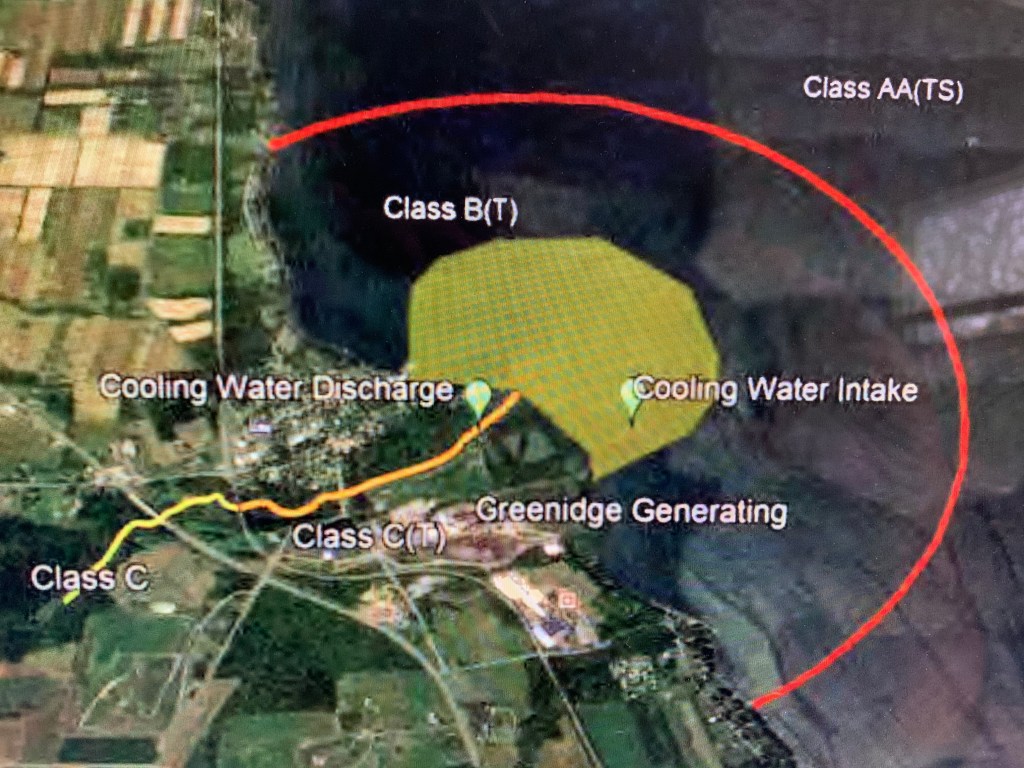

Today cooling water from Seneca Lake enters the plant through a seven-foot diameter intake pipe that extends 650 feet offshore into water 11 feet deep. “The pipe withdraws water from a 27-ft x 27-ft steel intake structure composed of 3/16-inch bars on 6-inch centers,” the company said in a 2019 report. “There are no traveling screens … Reversing valves on the condenser automatically wash out any (aquatic) debris that might accumulate on the condenser tube face.”

The once-through cooling system discharges its heated water into Keuka Outlet, but data are scare on exactly how heated. According a schedule Irwin submitted to the DEC in September, Greenidge’s thermal study of the bay won’t be finished until 2022.

In the interim, informal temperature monitoring by volunteers associated with CPFL between Aug. 6 and Sept. 2 showed readings topping 100F degrees in the Keuka Outlet — 30F degrees above the level for which the DEC urges “precautions.”

Black, the Dundee fisherman, said he’s not sure how much the Dresden power plant has contributed to the decline in his fishing success.

He said he suspects that the two salt plants near Watkins Glen, which have DEC permits to discharge millions of gallons of brine into the lake, may be doing even more damage than Greenidge. (Seneca Lake provides drinking water for roughly 100,000 people, but it is easily the saltiest of the 11 Finger Lakes. Even processed drinking water drawn from Seneca is not recommended for those on extreme low-salt diets.)

Black said he would like the DEC become more proactive in determining why Seneca Lake fishing has been on the decline. “On the same dock where I used to see perch by the hundreds, I see none,” he told the Torrey officials Tuesday. “I used to catch rock bass, bluegills. I see none of those any more.”

Torrey Highway Superintendent Tim Chambers responded: “Maybe you’re not fishing right.” Chambers, who said he’d fished around Dresden since the 1950s, said his fishing was still “good.”

Anglers’ experiences obviously vary. A pair of fishermen who posted on the National Lake Trout Derby Facebook page in May expressed frustration similar to Black’s.

“Pretty sure there aren’t any fish in Seneca Lake …. Didn’t mark a damn thing yesterday. Hoping we have better luck today!” Andrea Ridley posted.

“Been 2 yrs in a row Seneca stumped me,” wrote Art Guillery. “I’m from Lake George. I do well on Skaneateles, Owasco and Cayuga. All my normals don’t work! Can’t figure it out.”

Nice job. As usual.

Mary Anne Kowalski. 315-759-3761

On Fri, Nov 13, 2020, 1:52 PM Water Front- Peter Mantius wrote:

> Peter Mantius posted: ” DRESDEN, Nov. 13, 2020— A local fisherman is > urging Torrey town officials to consider the declining state of Seneca > Lake’s fish before they approve Greenidge Generation’s planned expansion of > its Bitcoin mining data center. “The fishing’s gone to hell” >

LikeLike

Liked your article. Long family history on both Seneca lake and Keuka. Grew up fishing the outlet. Finger family on Seneca and Flynn family on Keuka. Cottages on both for generations. Fished heavily on both my whole life. Keuka health is fantastic. Fishing, snorkeling, swimming despite invasives is unbelievable. Seneca in the past 10 years has become devoid of fish life, Point coming. Dresden warm water discharge not the problem. Anglers flocked to fish that stretch of the outlet for decades. Salt mine discharge have heard about it since the early 80’s. Never saw a problem in Seneca. Elephant in the room is runoff from the wineries. Period. I live out of state and am not dependent on that industry and totally understand why it is not in the picture politically but the gigantic algae bloom I ran through in the boat at the end of Glenora a few years ago made it very clear to me. Goes on every late summer. Advocate for using resources available to solve the runoff of fertilizer, pesticides and herbicides into Seneca lake without harming the winery economy is the holy grail. Not pretending to have the answer but bit players like Dresden power plant and salt mine runoff are a tiny fraction of the issue in my favorite Finger lake. Seneca

LikeLike