CAMPBELL, Aug. 11, 2023 — A senior state regulator said Thursday that any town law that purports to ban the practice of spreading municipal sewage sludge on farmland risks running afoul of the state’s “very strong” Right to Farm law.

“Biosolids recycling (sludge spreading) is protected under Right to Farm,” said Sally Rowland, an Albany-based environmental engineer with the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

Rowland offered a broad defense of the practice at a public hearing called by the Thurston Town Board, which plans to consider a total ban on sludge spreading next week.

“The premise of our (DEC) program … is that these materials are beneficial to farms,” she added. “It is not a waste disposal activity.”

Several speakers vehemently disagreed, based on their experiences living near Leo Dickson and Sons’ 2,700-acre sewage spreading operation in and around Thurston. Wayne Wells argued that the DEC has enabled the Dickson family for decades in support of “a state bureaucratic policy need to dispose of poisonous sewage.”

Recent uncertified tests of water wells around the Dickson fields showed that most had traces of PFAS “forever chemicals.” Last year Maine banned sludge spreading on fields after crops and animals at several farms that had relied on sludge were found to be contaminated with PFAS.

After Maine’s law curtailed Casella Organics’ operation in that state, the company quietly bought or leased Dickson’s sludge-spread fields on Bonny Hill in Thurston. Town officials didn’t immediately learn about the transactions. But when the Town Board discovered them, it promptly enacted a moratorium on new or expanded waste management facilities.

The DEC is currently evaluating two related applications: one to transfer Dickson’s sludge spreading permit to Casella Organics and another to add a major new supplier of Long Island sewage sludge. Thurston Town Supervisor Michael Volino says those actions would violate his town’s waste moratorium.

Final permitting decisions fall to the DEC’s Region 8 office, headed by Tim Walsh, who was present at Thursday’s hearing. He declined repeated requests to inform several dozen people in the audience of the status of the applications.

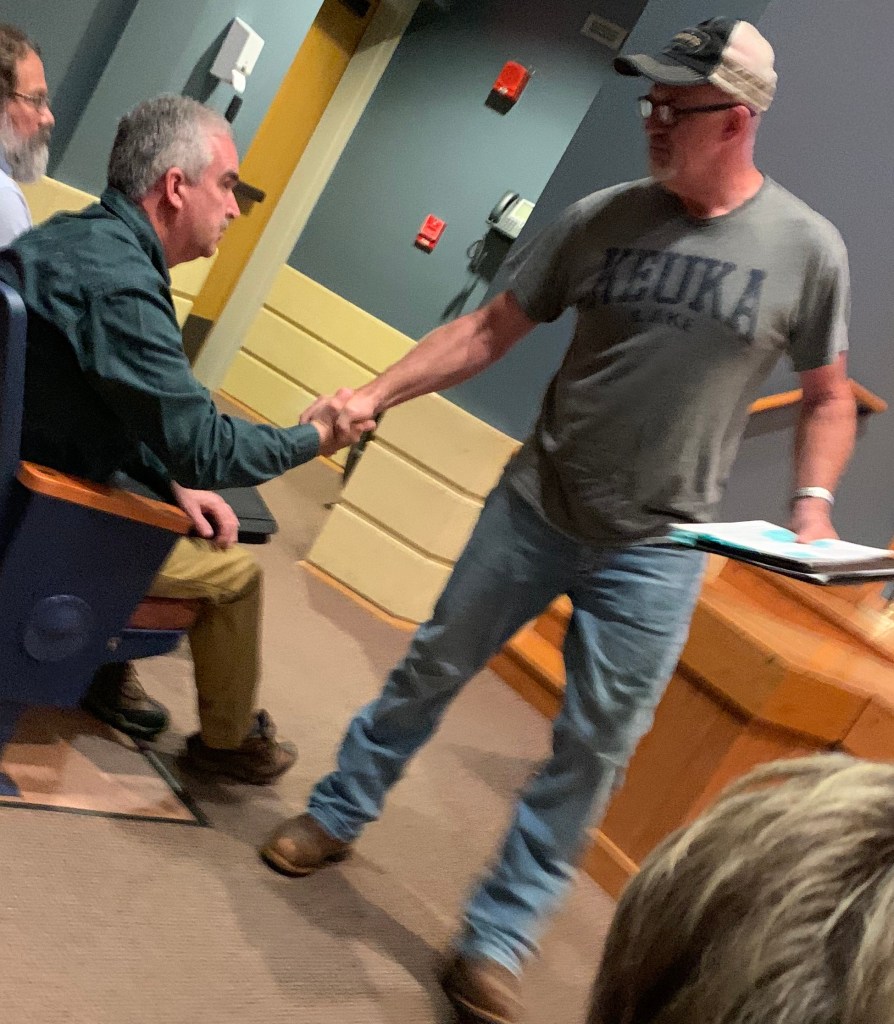

“Come up here and address these people. Tell them what’s going on,” Tim Hargrave, a Thurston farmer, urged Walsh from the speakers’ podium. Walsh didn’t reply or budge.

Rowland, a 37-year DEC veteran with a Ph.D from RPI, carried the speaking load for the DEC. Volino had introduced her as a representative of Gov. Kathy Hochul.

Hochul had previously urged Walsh to respond to emails from Thurston officials about the status of the Dickson/Casella waste applications.

Walsh’s June 23 letter to Thurston Councilmember Holly Chase hinted that his office was leaning toward granting approvals, stating: “Dickson’s pending modifications do not involve any physical expansion of operations or an increase in the amount of biosolids or other waste the facility can currently accept, store, or land apply.”

Volino disagreed, saying the addition of the Bay Park sewage treatment plant in Nassau County “has the potential to double the land spreading operation on Bonny Hill.”

Volino also said he was alarmed that Hochul wants to dramatically increase land spreading of sludge statewide in coming years, according to the state’s draft solid waste plan.

The first bullet point in that plan’s “vision” calls for reducing waste sent to landfills by 85 percent by the year 2050. To achieve that vision, biosolids recycling would need to increase from 22 percent in 2018 to 57 percent in 2050, according to the plan.

Even so, Rowland said Thursday “it’s not really the case” that the governor is pushing to significantly increase biosolids spreading on fields.

“It doesn’t mean we’re pushing it, obligating it, in any way shape or fashion,” Rowland said. “If it happens, it happens. If it doesn’t, it doesn’t.”

A skeptic might ask: “Same with the vision?”

Rowland also said New York is poised to announce new PFAS standards for biosolids that will involve limits on industrial wastes in sewage sludge.

She implied that Maine was hasty when it enacted its total ban on sludge spreading. The initial farm that was found to have high PFAS levels had applied paper mill sludge, not municipal waste sludge, Rowland said.

“They (Maine officials) didn’t take the time that we will to dig a little deeper to see what the issue was, and they said we’re just going to ban land application,” she said.

Other scientists have a much darker view than Rowland of the dangers of municipal sewage sludge.

Murray McBride, an emeritus professor at Cornell University who specializes in pollutants in agricultural soil, wrote in a June 28 formal comment on the state’s solid waste plan:

“PFAS ‘forever chemicals’ are being found on farms, in well water, and in vegetable crops and dairy food products where biosolids had been applied, sometimes decades earlier.”

McBride added that present rules for sludge spreading do not protect farmland, farmers or the general public. “Instead, farmland application provides a direct pathway for contamination of food crops, meat, and dairy products with persistent organic toxins, including hundreds of PFAS compounds.”

At the hearing Thursday, Brett Dickson, spoke in defense his family’s long-time use of sewage sludge.

“I chose to use biosolids to fertilize my crops and nothing bad has happened,” he said. “No, I’m not for polluting anybody’s well. If it can be proven, and I do mean proven, that it came from me, then I would definitely have a totally different tune.”

Tim Hargrave said the Dickson family has a history of flouting DEC rules. He said the agency has cited it for failure to keep proper records, for use of unregistered fields, for spreading too close to water wells, and for accepting waste for non-approved sources.

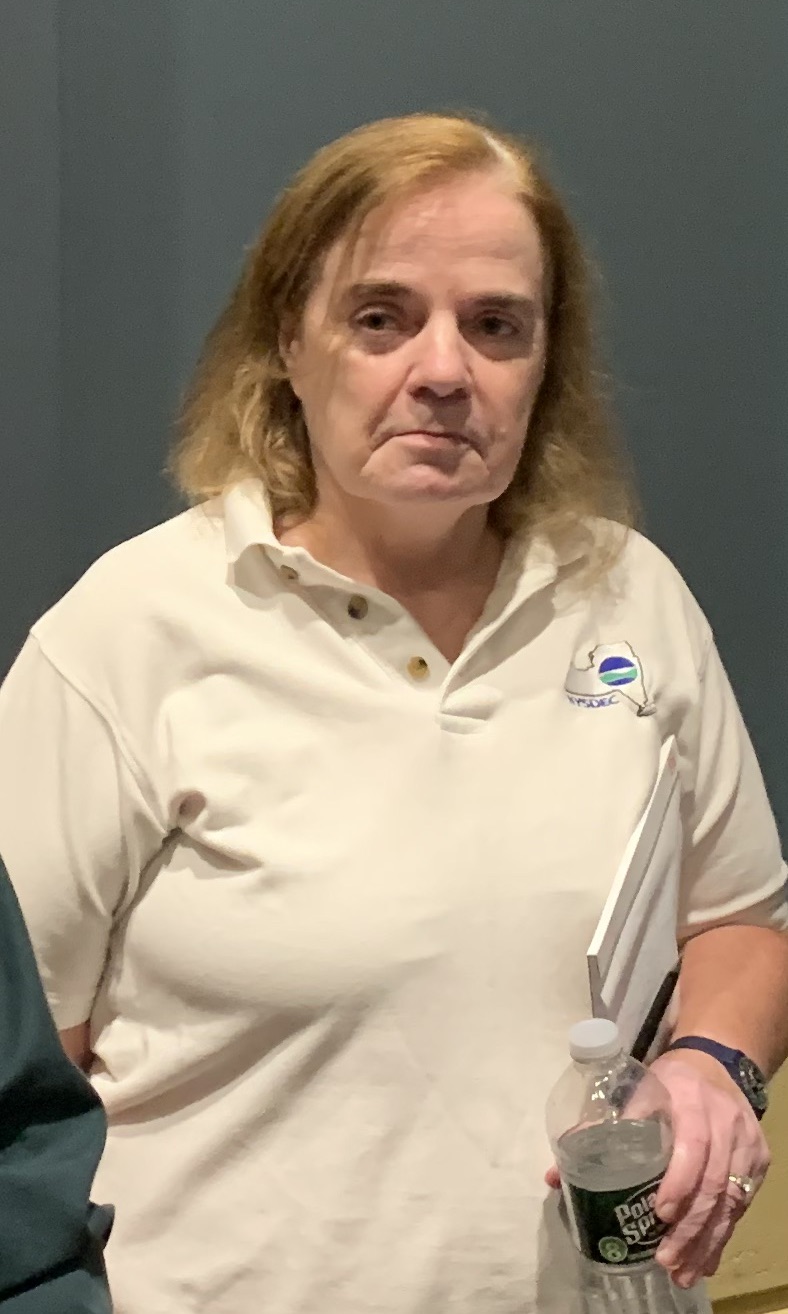

Eva Turner voiced her lack of confidence in DEC enforcement.

“I bet you if I went to Cameron and started throwing toxic chemicals on rattlesnakes, they’d (DEC officials) be after me,” she said. “They’ll protect them rattlesnakes. They’ll just make everything perfect for them. But not for us.

“If everything’s so safe, why are there so many wells on Bonny Hill that are contaminated? I would hope that my life would be more precious than rattlesnakes.”

good reporting on a very contentious issue. Sally Roland said she presented Prof. Murray McBride’s research and conclusions that sewage sludge/biosolids should not be used on farmland to other scientists who disagreed with McBride’s opinions. Which scientific opinion do you think would be favored by now bankrupt farmers in the States of Maine and Michigan who have had their cattle destroyed and their family’s health compromised? How can Sally Roland (Albany DEC ) say with a straight face that sewage sludge/biosolids are “Safe”?

LikeLike