THURSTON, Nov. 8, 2022 — A unit of Casella Waste Systems Inc. has acquired or leased 2,789 acres from a Steuben County farming family that has spread sewage sludge on the properties for decades, a practice Casella plans to continue.

County land records show Casella Organics acquired 126 acres and obtained 10-year leases on 34 additional tracts totaling 2,663.7 acres from Leo Dickson & Sons Inc. or its affiliates in July.

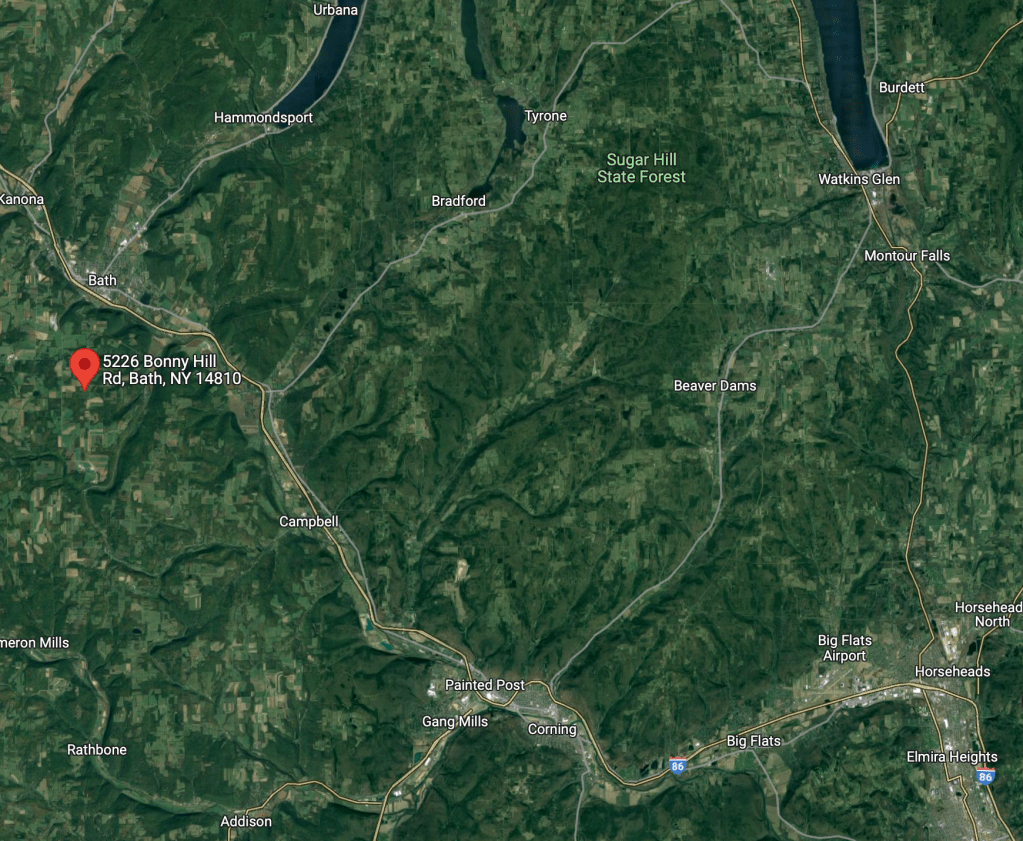

The Dickson firm, based in Thurston about 10 miles northwest of Corning, spread sludge on 2,061 acres in 2018, according to its 2019 annual report filed with the state. It grows a variety of crops on the land, including corn, alfalfa and soy beans.

Sewage sludge is residual waste produced by sewage treatment plants or food processors.

The Dickson firm is authorized to accept so-called “biosolids” from more than two dozen wastewater treatment plants, including several in the Finger Lakes: Cayuga Heights, Dryden, Dundee, Perry, Trumansburg and Watkins Glen.

For decades, farmers across the country have been spreading sludge on fields used to grow hay or other crops, most of which are fed to cattle. But recent evidence showing the sludge is often contaminated with PFAS ‘forever’ chemicals has made the practice highly controversial in several New England states.

In Maine, several dairy herds that fed off sludge-spread fields produced milk that was too contaminated to sell. The Maine Legislature enacted a law in April that categorically bans the spread of sewage sludge on fields.

“No one can undo the historic contamination of our land,” Adam Nordell, co-owner of a PFAS-stricken farm in Unity, told The Maine Monitor. “But we know enough now to turn off the tap.”

New York does not systematically test sewage sludge for PFAS, a class of thousands of common man-made chemicals used to make cookware, water-resistant clothing, stain-resistant furniture and dozens of other household items. They are toxic in doses as low as a few parts per trillion and are long-lasting.

New York is in the process of regulating several common PFAS compounds found in drinking water, but it hasn’t required systematic testing for PFAS in landfill leachate or sewage sludge.

Sludges, which are notably smelly, are often sent to landfills if it not spread on remote fields.

Casella Organics claims to process and compost sludge before distributing it to farmers, landscapers and homeowners.

“Casella has worked with the Dickson family for a long time and is delighted to have acquired this piece of land,” Clark James, director of operations for Casella Waste Systems, said in a Nov. 7 email to WaterFront. “We are still in the planning stages, but ultimately we expect that the property will continue to support traditional beneficial reuse activities for Casella’s customers in the region.”

Some residents of Thurston have expressed concern that Casella might eventually convert its acquired property into a new landfill.

Michael Volino, a member of the Thurston town board, said the matter is on the agenda for the board’s regular meeting Nov. 9. “We are just going to decide how to move forward with a local law prohibiting landfills,” Volino said.

But Larry Shilling, Casella’s regional supervisor who oversees the Hakes, Hyland and Ontario County landfills, dismissed the possibility of a future landfill at the site.

“It’s not about a landfill at all,” he said. “It would be used for land spreading and processing of organic materials. But I’m not in charge of (Casella) Organics. I have no say in what they do or don’t do. If it were going to be a landfill, I would know about that.”

Casella Organics, which has produced a video that touts its efforts to reuse sewage waste in beneficial ways, opposed the Maine legislation banning sludge spreading.

In fact, the new law, LD1911, directly threatens Casella Orgainics’ Hawk Ridge composting facility, about 20 miles northeast of Augusta, according to Sarah Woodbury, director of advocacy at the non-profit Defend Our Health.

Woodbury noted that an early version of the bill would have applied PFAS screening standards to sludge-based compost.

“However, based on testimony of the (Maine Department of Environmental Protection) … nearly all sludge and sludge-derived compost already fails the screening standard,” Woodbury said in April. The DEP felt that once those standards were made even more stringent, virtually all sludge and sludge compost would fail, she added. That testimony led legislators to amend the bill to simply ban the use of sludge as a fertilizer or in compost.

In arguing against the bill, Casella officials sought more lenient PFAS standards and asserted that landfills didn’t have adequate space to take on the sludge that has routinely been spread on fields. Other officials disputed the landfill capacity argument.

In the Finger Lakes, after the Casella-operated Ontario County landfill began accepting large quantities of sewage sludge several years ago, local residents complained that odors became far more offensive.

Last week the state Department of Environmental Conservation fined the company and Ontario County $500,000 for exceeding odor limits and other violations over several years.

The landfills’ 2021 annual report stated that it had accepted 57,254 tons of sewage sludge the previous year.

Phillip Dickson, president of Leo Dickson & Sons, did not return a phone call requesting an interview.

Great work Peter. Thank you.

LikeLike