GENEVA, May 1, 2023 — This coming Memorial Day weekend, anglers will converge on Geneva — the so-called “Lake Trout Capital of the World” — to compete in Seneca Lake’s 59th annual National Lake Trout Derby.

Contestants from around the country will compete for $30,000 in prize money for record-weight trout and salmon.

While many will later make dinner out of their catches, only a few are likely to be aware of disquieting news about recent tests confirming that Seneca Lake fish are highly contaminated with PFAS ‘forever chemicals.’

The good news is that PFAS levels in the tested samples from the 2022 Derby fell below the state’s health advisory levels and far below its “DO NOT EAT” warning level for fish.

The bad news is that those state Department of Health consumption guidelines ignore the latest scientific findings and are more protective of anglers’ habits than their health.

Even the scientists who recently quantified the contamination levels of Seneca fish took refuge in the DOH guidelines and were careful to put their results “in context” by emphasizing the nutritional benefits of the fish.

“We want people to keep fishing these lakes and we want them … to be eating the fish from nature that’s freely available,” Roxanne Razavi, an assistant professor at SUNY’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry, said at the conclusion of a recent webinar.

Minutes earlier, Razavi had said: “I want to thank … all the anglers that let us use part of their meal — their dinner — for our research….

“Our take-away, our main finding was the Seneca Lake lake trout have the highest PFAS exposure among all the species that we looked at from the Derby.”

On average, the lake trout SUNY-ESF tested contained PFAS chemicals at more than a thousand times the concentration that the state deems safe in public drinking water.

The latest scientific research shows PFAS chemicals — a class of more than 10,000 man-made compounds used to make everyday products that are non-stick, stain-resistant and waterproof — are a serious health hazard even when measured in only a few parts per trillion.

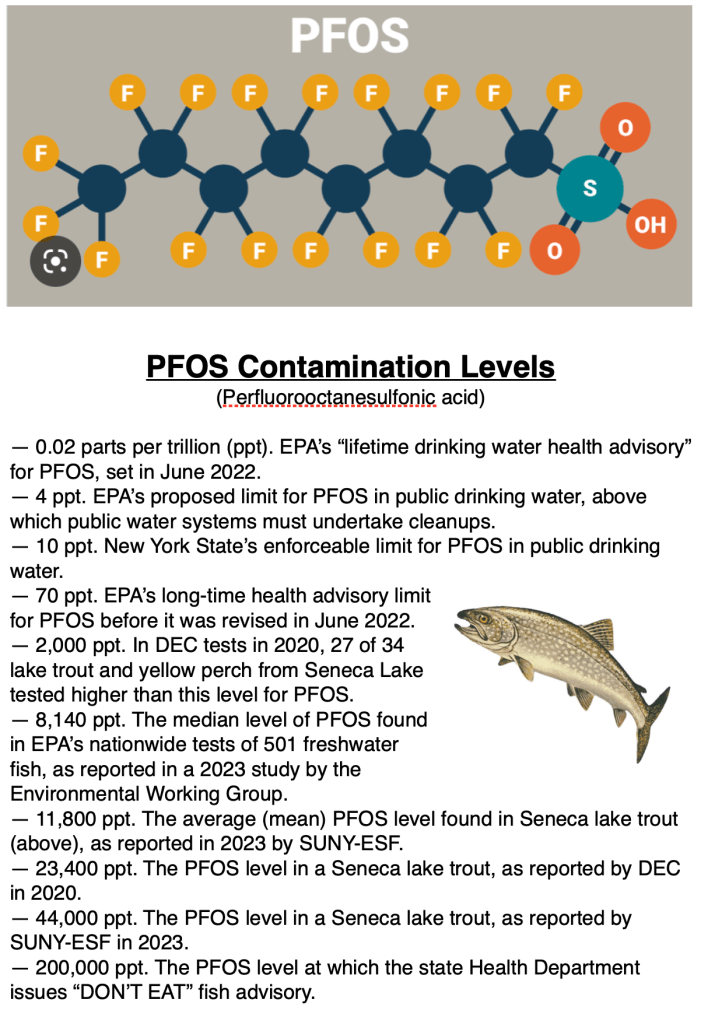

The DOH recently required public water utilities statewide to undertake expensive fixes when tap water they produce exceeds 10 parts per trillion for either of two PFAS compounds: PFOS and PFOA.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently proposed even lower enforcement levels for those two chemicals: 4 ppt. When EPA finalizes that rule, New York will be obliged to match the federal contamination limits for tap water.

By contrast, Seneca lake trout were found to have, on average, total PFAS chemicals of 26,100 ppt. The mean level of PFOS alone was 11,800 ppt.

Remarkably, the state health department does not consider those results to be potentially risky for those who consume fish. It urges people to eat up to four meals a month of any fish that registers PFOS at less than 50,000 ppt. It doesn’t recommend completely avoiding consumption of a fish until it clocks in at 200,000 ppt. or more.

The DOH has declined to explain why its contamination limits diverge so markedly for fish New Yorkers eat versus tap water they drink. (The agency recently provided explanations for state fish advisories in response to questions emailed by WaterFront.)

Asked by WaterFront if there is a difference between eating or drinking PFAS contamination, Linda Birnbaum, a former director of the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences, said:

“No. Both are routes of ingestion. Whether you eat it or drink it, PFAS (chemicals) go to the same places in the body and do the same thing…We do need appropriate fish advisories and regulation of what’s in our food.”

Betsy Southerland, a former director of the Office of Science and Technology at the EPA’s Division of Water, said states are not adequately advising the public about the health risks of eating freshwater fish.

In a recent opinion column, Southerland wrote that the goal of the 1972 Clean Water Act to make the nation’s waterways “fishable and swimmable” is now “unachievable” due to toxic PFAS discharges into rivers, lakes and streams that have contaminated most aquatic life.

To slow the damage, the states and the EPA need to set PFAS limits on discharges from industries, landfills and wastewater treatment plants, she said. Meanwhile, anglers deserve more accurate fish consumption advisories.

“I think they (state and federal regulators) are terrified that if they actually go after this, they’ll be saying no (freshwater) fish in country can be eaten,” Southerland told WaterFront. “The entire freshwater fishing industry would have to survive on catch-and-release. I think it’s that serious.”

On the other hand, the incentive to radically lower fish health advisory levels is reduced by the fact that the vast majority of Americans don’t catch or eat freshwater fish regularly.

Only about 5 percent of adults in the U.S. are high-frequency consumers of fish (three or more meals per week), a 2017 study found. Nearly 90 percent of those eat fish from restaurants or commercial markets, which have dramatically lower PFAS levels than self-caught freshwater fish. The study estimated that recreational anglers who are high-frequency seafood consumers total somewhere between 1.9 million to 2.8 million.

The state DOH says it’s safe to eat up to four half-pound servings of non-commercial freshwater fish a month unless specific advisories warn against it.

If the PFOS concentration in a fish exceeds 50,000 ppt, consumption should be limited to once a month. Certain advisories may be more stringent for pregnant women and young children. Only fish with PFOS above 200,000 ppt should never be eaten by anyone, DOH says.

But the state has fully-analyzed PFOS data on fish from only three of the 11 Finger Lakes.

Although the first PFAS chemicals were developed in the 1930s, health concerns didn’t mount until the 1970s when the compounds were found in the blood of those working with them.

In the early 2000s, PFAS manufacturers, including 3M, began phasing out compounds like PFOS (while producing new, untested alternatives). Late last year, 3M said it planned to phase out the manufacturing of all PFAS chemicals by 2025, even as it continues legal battles.

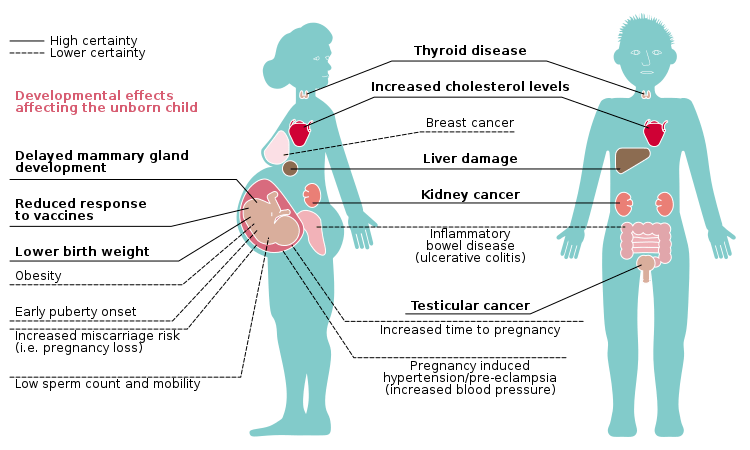

In recent years, thousands of scientific studies on the health effects of PFAS compounds have documented links to kidney and testicular cancer, liver damage and a host of other ailments. The EPA and other regulatory agencies have been setting increasingly stringent limits in response to new developments.

“It presents a huge challenge to regulatory agencies and environmental toxicologists to understand these chemicals and their movement in the environment and the health implications,” said Razavi of SUNY-ESF.

In January, a widely-reported study concluded that non-commercial freshwater fish were far more contaminated with PFAS chemicals than fish sold at commercial markets or restaurants.

In that study by scientists from Duke University and the Environmental Working Group (EWG), the median level of PFAS in 501 EPA samples of freshwater fish caught from 2013-2015 was 11,800 ppt.

The researchers found that eating just one “average” fish can be equivalent to drinking for a month water contaminated with PFOS at 48 ppt (almost five times New York State’s enforceable limit for tap water).

Even infrequent consumption of the freshwater fish can increase blood serum levels of PFOS, they found.

Razavi noted that PFOS levels in Americans’ blood have declined sharply in recent years, presumably because 3M began phasing out the manufacture of its product 20-odd years ago.

“This is a good news scenario,” Razavi said during the Apr. 26 webinar.

But eating just one contaminated freshwater fish quickly skews that trend.

On average, Americans had PFOS in their blood at 4.3 ppt in 2018. One person in 20 registered as high as 14.6 ppt.

Eating the “average” fish in the Duke-EWG study once a month would raise contamination levels in blood by 11.07 ppt, Duke-EWG scientists calculated. (The “average” Duke-EWG fish had PFOS of 8,410 ppt, while the “average” SUNY-ESF lake trout had 11,800 ppt.)

Eating the average Duke-EWG fish weekly — as the New York DOH recommends for any fish registering under 50,000 ppt — would raise blood contamination levels by 47.96 ppt, the Duke-EWG researchers said.

Those theoretical calculations are backed up by real world data. A 2022 study of anglers near Onondaga Lake found that the most frequent consumers of freshwater fish had median levels of PFOS in their blood at 9.5 times the U.S. median.

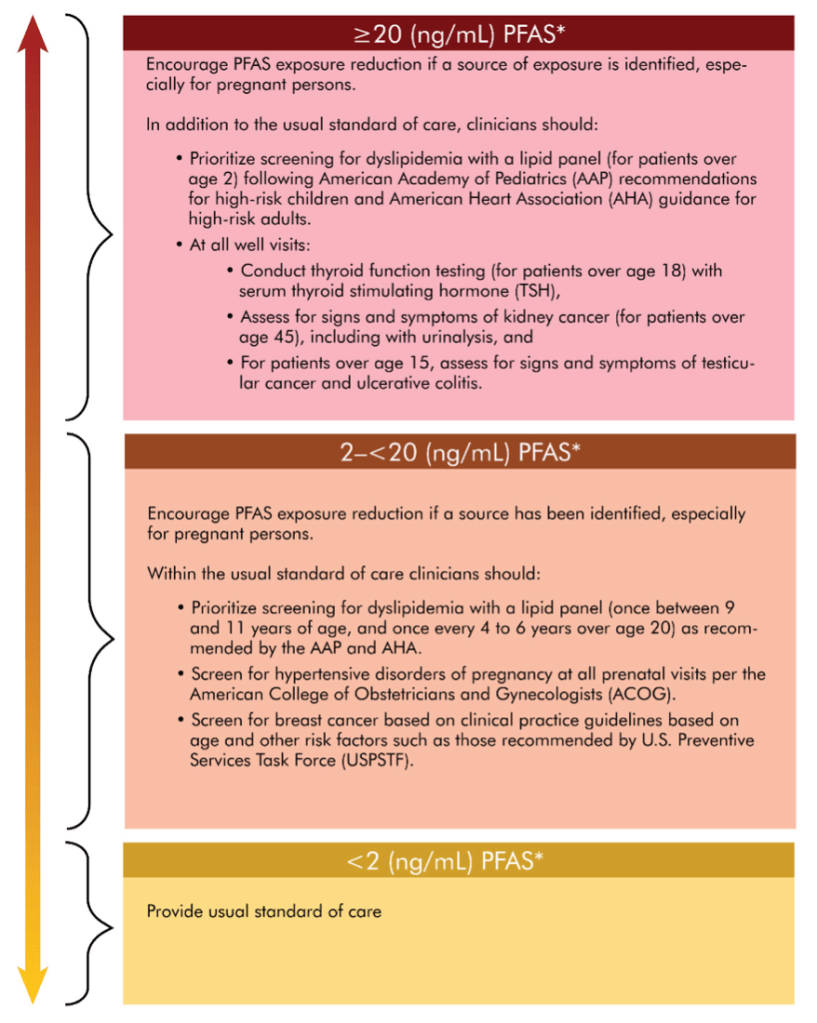

People who test between 2 ppt and 20 ppt for total PFAS in their blood face “potential adverse effects,” according the National Academies of Sciences.

When PFAS blood levels exceed 20 ppt, clinicians should encourage patients to identify and reduce PFAS exposure, the NAS reported last July. In addition, it recommended that those patients should be screened for thyroid problems, given urine tests for kidney cancer and assessed for signs of testicular cancer and ulcerative colitis.

Despite the established correlations between consumption of PFAS-contaminated freshwater fish and sharply higher PFAS in blood, fewer than one-third of the states have any fish consumption advisories at all.

New York’s 200,000 ppt “DO NOT EAT” advisory is similar to consumption advisories in Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

“New York uses the Great Lakes Consortium’s risk assumption advisories,” Wayne Richter, a monitor with the state Department of Environmental Conservation’s Division of Fish, Wildlife and Marine Resources, said during the Apr. 26 webinar.

Those state advisories are based on the EPA’s now-outdated lifetime health advisories for exposure to PFOS and PFOA of 70 ppt. Last year the agency dramatically lowered those limits to 0.02 ppt for PFOS and 0.004 ppt for PFOA.

If states followed the latest EPA exposure guidelines, they would have to set their “DO NOT EAT” consumption guidelines at 79 ppt — not 200,000 ppt — the Duke-EWG researchers calculated.

“If fish advisories were updated to reflect this interim (EPA) health advisory, nearly all freshwater fish collected by the EPA from 2013 to 2015 (the data used in the Duke-EWG study) would be considered unsafe to eat,” the Duke-EWG study said.

Southerland agreed. But she added that setting guidelines that low would be disastrous for the freshwater fishing industry, particularly in the Great Lakes.

“The EPA has been doing random sampling (of PFAS in fish since 2008), and it’s clear the Great Lakes are higher than anybody else,” said Southerland, who was featured in Frontline’s 2018 report on the Trump Administration’s EPA. “I think it would be rare to find a situation within the Great Lakes where the fish were under (the contamination level calling for) limited consumption.

“So I think the Great Lakes would be really hurt by this.”

So far, New York State has very limited data on PFAS compounds in fish in the Finger Lakes, and the DOH’s regional fish advisory ignores them entirely.

Speakers at the April 26 webinar said DEC plans extensive testing this summer at all 11 lakes except Canandaigua and Skaneateles.

In response to the Duke-EWG study’s release in January, WaterFront filed an open records request for all state data on PFAS tests of fish in the Finger Lakes. The agency provided data on only three of the 11 lakes — Seneca, Otisco and Canadice. It said it had preliminary data from Cayuga and Hemlock lakes that it was not willing to release.

The DEC’s 2020 study of 19 lake trout and 10 yellow perch from Seneca Lake found they had significantly higher PFAS concentrations than fish from Otisco and Canadice, as WaterFront reported in March.

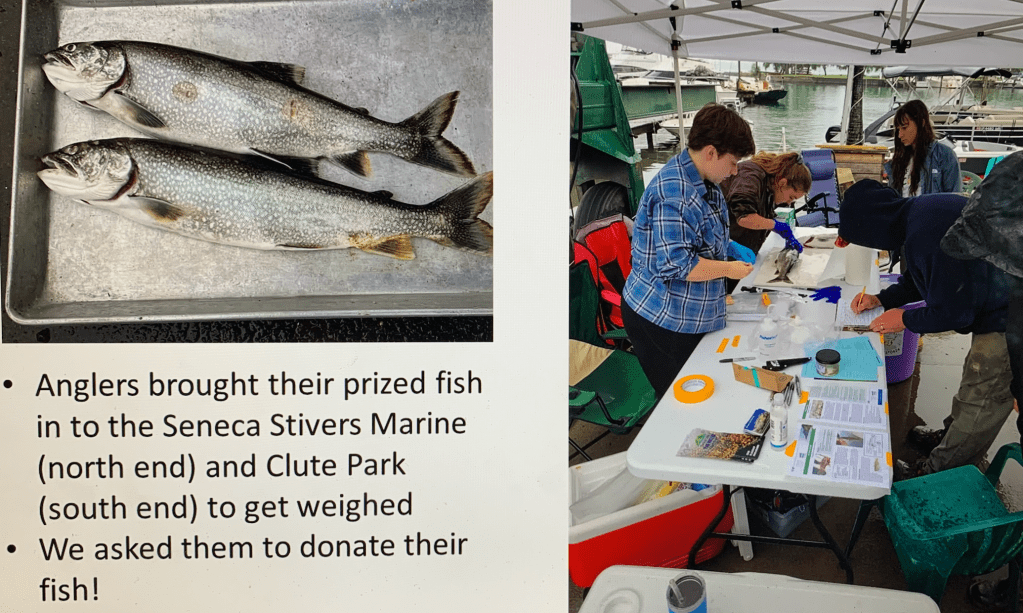

The results from the 2020 DEC study and from the recent SUNY-ESF study were roughly similar, Razavi said.

SUNY-ESF tested Seneca Lake samples of 10 lake trout, nine brown trout, six rainbow trout and five landlocked salmon. The lake trout registered the highest concentration levels for PFOS, PFNA, PFDA and PFOA.

Razavi noted that Seneca’s concentrations of PFNA, PFDA and PFOA were sharply higher than the concentrations in fish from lakes Canadice, Erie and Ontario. Those findings suggest the Seneca may have one or more unique sources of PFAS pollution, she said.

The former Seneca Army depot — a known PFAS hot spot — is a likely suspect. But abandoned industrial sites around Dresden and Geneva might also be possible sources, Razavi acknowledged.

The Finger Lakes Institute in Geneva and Seneca Lake Pure Waters Association participated in the SUNY-ESF study and will continue to research PFAS in the Finger Lakes.

The few anglers who have posted comments on social media about reports on the potential health effects of eating freshwater fish have tended to be dismissive. One poster wrote:

“More and more people are eating their catches these days. Funny, I just asked my 9-month old’s pediatrician if freshwater fish was OK for him to try, provided no (state) advisories. He said it was perfectly fine.”