WATERLOO, Oct. 18, 2022 — On May 3, Seneca Falls town officials ordered the Seneca Meadows Inc. landfill to stop pumping its leachate into the town’s sewer system.

During the previous week or more, several businesses near the landfill that straddles Waterloo and Seneca Falls had been reporting overpowering stench emanating from within their buildings.

The Seneca Falls sewer department suspected hydrogen sulfide gas from the discharged leachate was escaping into private sewer pipe systems, causing nearly intolerable odors from bathrooms that spread throughout buildings.

“It was so bad when I walked in this place, it took my breath away, gave me an instant headache,” said Randy Maestre, owner of Absolute Auto Repair on Route 414 in Waterloo. “My whole shop and the garage was just full of that smell.”

At neighboring Waterloo Container, Ed Brechue, Jodi Ocque and Cathy Fronczek said they suffered headaches and scratchy throats for more than a week from foul odors that one described as “like an animal had died in the wall,” another as “sickening waste.”

Wright Beverage, Napa Auto and Hampton Inn, among others, made similar reports, according to a May 4 letter to the Seneca County Health Department from Bill Lutz, owner of Waterloo Container.

After the landfill stopped pumping its leachate, as instructed, the indoor odors promptly subsided, and their intensity hasn’t spiked in the five months since even after SMI resumed its leachate discharges in late July.

“We halted the process until we could determine the cause of the excess hydrogen sulfide,” Seneca Falls Town Supervisor Michael Ferrara said Monday.

“We followed the (town’s) lead regarding their investigation, worked with them … and fully complied throughout,” said Kyle Black, manager of SMI, the state’s largest landfill.

The sewer gas incident caused hardly a public ripple, despite the fact that SMI is planning a controversial expansion that faces a public campaign to try to stop it.

Ferrara mentioned sewer gas briefly at one town meeting, but it passed unnoticed by local media and expansion plan opponents.

Even so, Lutz has continued to press for answers about what made his employees so sick in late April and early May.

He’s been dissatisfied with the official response, particularly to his questions about the health effects of lengthy, heavy exposure to hydrogen sulfide and, potentially, other harmful chemicals, including PFAS compounds. OSHA describes hydrogen sulfide as “a colorless, flammable, extremely hazardous gas.”

Lutz vented his frustration in an Oct. 11 letter to Dereth Glance, deputy commissioner of the state Department of Environmental Conservation.

“We asked the (county) health department to help us find answers,” Lutz wrote. “They told us to go to the DEC. We did, and here we are. Still in the dark.”

Scott King, director of public heath for Seneca County, had written Lutz on May 20: “Should the sewer odors recur inside your facility … immediately remove all personnel from the affected area.” King urged Lutz to “increase fresh air flow” and instruct those with acute symptoms to seek medical help.

A month later, King told Lutz that experts at state Bureau of Toxic Substances Assessment said “there is a wide separation between hydrogen sulfide nuisance odors, which are offensive and perhaps nauseating, and the level of odors that are considered likely to impact health.”

Furthermore, he added, sewer odors were an “unlikely” pathway for PFAS chemicals to harm people.

In any case, King wrote on June 17, “indoor air quality … is not within the primary jurisdiction of the Department of Health (state or local).” He urged Lutz to pursue the matter with the DEC and hire a professional to check his building’s wastewater plumbing.

Lutz did both. He said he paid a plumbing expert nearly $10,000 to learn that his waste system met relevant codes.

The DEC said OSHA (the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration) has primary responsibility for regulating indoor workplaces, including odors.

In a statement to WaterFront, DEC said its main role is to ensure that the town of Seneca Falls only accepts pre-treated leachate at its water treatment plant, which has a state permit to discharge into the Cayuga and Seneca Canal. The plant is not authorized to process raw leachate.

While the town sets rules to ensure that leachate discharges have, in fact, been pretreated, it has a financial incentive to keep the leachate flowing. It’s a money maker. For example, SMI paid the town $39,517 for accepting 1.47 million gallons of its treated leachate during the month of January.

Last year SMI produced 76.7 million gallons of leachate, the highly toxic runoff from rain that has percolated through the landfill’s massive mounds of garbage and waste. It is highly contaminated with PFAS chemicals (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), which both New York State and the federal Environmental Protection Agency have recently targeted as a major health risk.

Last year SMI shipped away 59.1 million gallons of untreated leachate, including 43.9 million gallons to the Buffalo Sewer Authority, according to the landfill’s 2021 annual report. It discharged 17.6 million gallons of treated leachate, or “permeate,” into the Seneca Falls sewer system.

Over the past decade, SMI has been investing millions of dollars in systems to treat its raw leachate at the landfill so it can avoid paying hefty fees to have it hauled away.

The landfill had been discharging raw leachate into the Seneca Falls sewer system until at least 2013, when it installed a reverse osmosis treatment system designed by the Rochem Group.

Since then it has added an “evaporator” to process leachate concentrate and a second reverse osmosis system with newer technology. The new Dynatec system began operating during a “startup phase” this summer.

The Rochem system was shut down to repair a “bad motor relay” and for cleaning on May 2 — the day before the town ordered SMI to halt discharges into its sewer system. It remained idle for at least the following two months, according to a July 7 email from the landfill’s William “Willie” Neuman to the DEC.

SMI engineer David Pannucci had provided further details in a June 10 letter to Ferrara.

“Fouling was found at the bottom of the (Rochem) permeate tank, which has been cleaned and removed,” Pannucci wrote. “This fouling may have contributed to H2S (hydrogen sulfide) odors in the Rochem permeate discharges.”

The Rochem system’s “degasser” unit, “wet well” and sewer lines connecting to the town sewer system also required cleaning and maintenance, Pannucci added.

While the Rochem system sat idle, the landfill turned to its evaporator to process raw leachate until it was destroyed by fire on Sept. 2.

SMI’s Black said Monday that both the Rochem and Dynatec reverse osmosis systems were operating, and the evaporator would be replaced.

Ferrara said the town was very satisfied that the leachate discharges are now being properly treated. “We get weekly reports and we monitor hydrogen sulfide levels at the source of our sewer line,” he said.

Even so, a co-founder of the environmental group Seneca Lake Guardian said the DEC should take a more active role in monitoring the discharges that the Seneca Falls treatment plant accepts, especially for PFAS.

Yvonne Taylor noted that because both the landfill and the town have financial incentives to be less than rigorous on ensuring leachate treatment, the DEC should verify compliance by requiring the Seneca Falls plant to report PFAS levels in its own discharges to the canal.

“That’s exactly what Sen. (Rachel) May’s bill would do, and why we need it so desperately,” Taylor said of Senate Bill s9525, which the Syracuse Democrat introduced in August. “Right now there are no responsible regulations for detecting PFAS discharged into our waterways.”

May’s bill would require all public water treatment plants to submit annual reports listing PFAS levels in their discharges into state waterways.

In 2018, the DEC required SMI and other landfills to test for PFAS in their leachate. All were highly contaminated with PFOA, one of the more common of several thousand PFAS chemicals that threaten human health — even in tiny concentrations.

In June, the EPA issued a health advisory alert for PFOA of 0.004 parts per trillion in drinking water. New York State now requires water utilities to remediate their systems if PFOA in their tap water exceeds 10 ppt. The state is currently finalizing rules that would apply that enforceable 10 ppt limit to a total of six PFAS compounds.

The 2018 TestAmerica tests showed that SMI’s raw leachate contained PFOA and seven other PFAS compounds at well over 1,000 ppt — 100 times the state’s enforceable limit for drinking water and 250,000 times the EPA’s health advisory level for PFOA.

The tests showed SMI’s treated leachate had much lower levels of PFAS than its raw leachate or leachate concentrate, which had PFAS readings as high at 15,000 ppt.

The DEC hasn’t required the landfills to update the 2018 tests. And the agency accepted a 2021 annual report from SMI that ran 551 pages without mentioning PFAS.

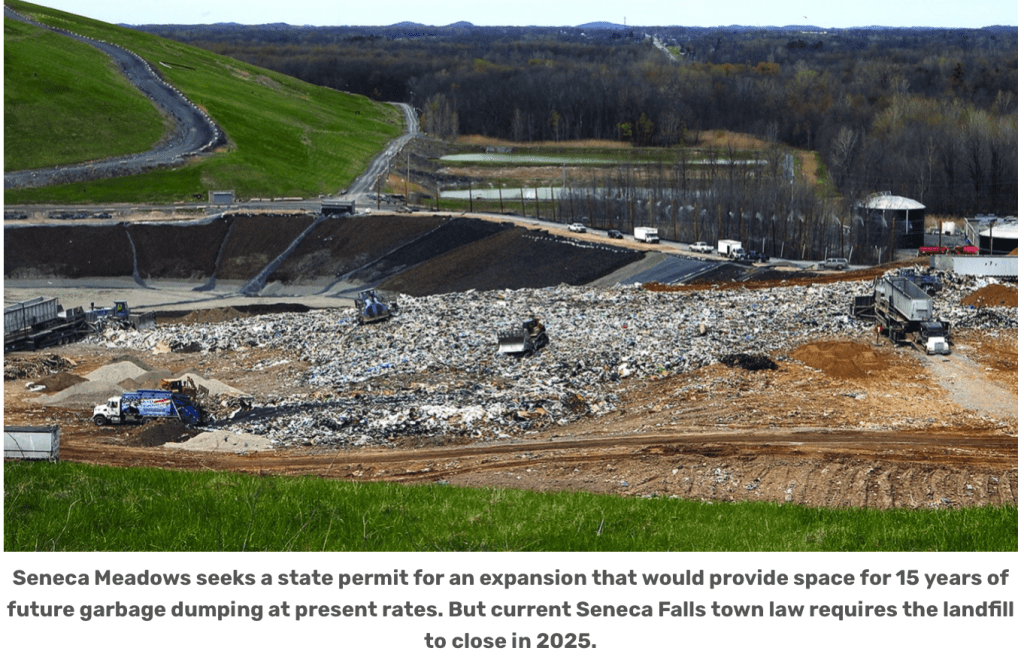

Meanwhile, SMI has applied to the DEC for a permit to expand substantially in spite of a Seneca Falls town law that requires the landfill to close in December 2025.

The landfill has filed suit challenging the town law, and a court hearing is scheduled for Nov. 1 in Waterloo.

Black has expressed confidence the landfill will operate well beyond 2025.

“I’m sure everybody’s seen a lot of Google alerts about our imminent closing in 2025, and frankly that’s just not going to be the case,” Black told Ulster County officials in March.

Under the proposed “Valley Infill” expansion, SMI would add capacity over the existing 26-acre Tantalo Inactive Hazardous Waste Site and raise the landfill’s height by 69 feet. If approved by the DEC, the expansion could extend the life of the landfill to 2040.

Seneca Lake Guardian has cited landfill odors and “PFAS-laden leachate” among the reasons the agency should deny the permit.

But town voters elected two new town board members in November who have voiced support for extending the landfill’s life. That left the five-person board with only one staunch defender of the law that mandates the 2025 closing date.

Days before the 2021 election, SMI’s parent company, Texas-based Waste Connections, wrote a $200,000 check to a group supporting the pro-landfill candidates. The town remains sharply divided into pro- and anti-landfill camps.

Maestre of Absolute Auto described an exchange he had with a friend who, while working at SMI, had caught wind of his odor complaints:

“He said, ‘Hey, I hear you hate the landfill.’ And I said, ‘I don’t hate the landfill. I’m just tried of the freakin smell, dude.’”

Farm life daily

Best regards, John Miller M: 917 847 0035 Hope for today. Confidence in tomorrow.

>

LikeLike

Peter, please don’t ever stop what you are doing. It is a blessing and a necessity.

LikeLike