SENECA FALLS, June 28, 2023 — The unusually high number of lung cancer cases around northern Seneca County over a five-year span caught the attention of the state Department of Health.

The 70,226 residents inside a 25-mile-wide circle touching Geneva and Auburn had 50 percent more lung cancer than expected during the years 2011-2015. Statistically, there should have been around 288 cases. There were 433.

So the agency classified the area as a lung cancer “cluster” and labeled it LU-H-17.

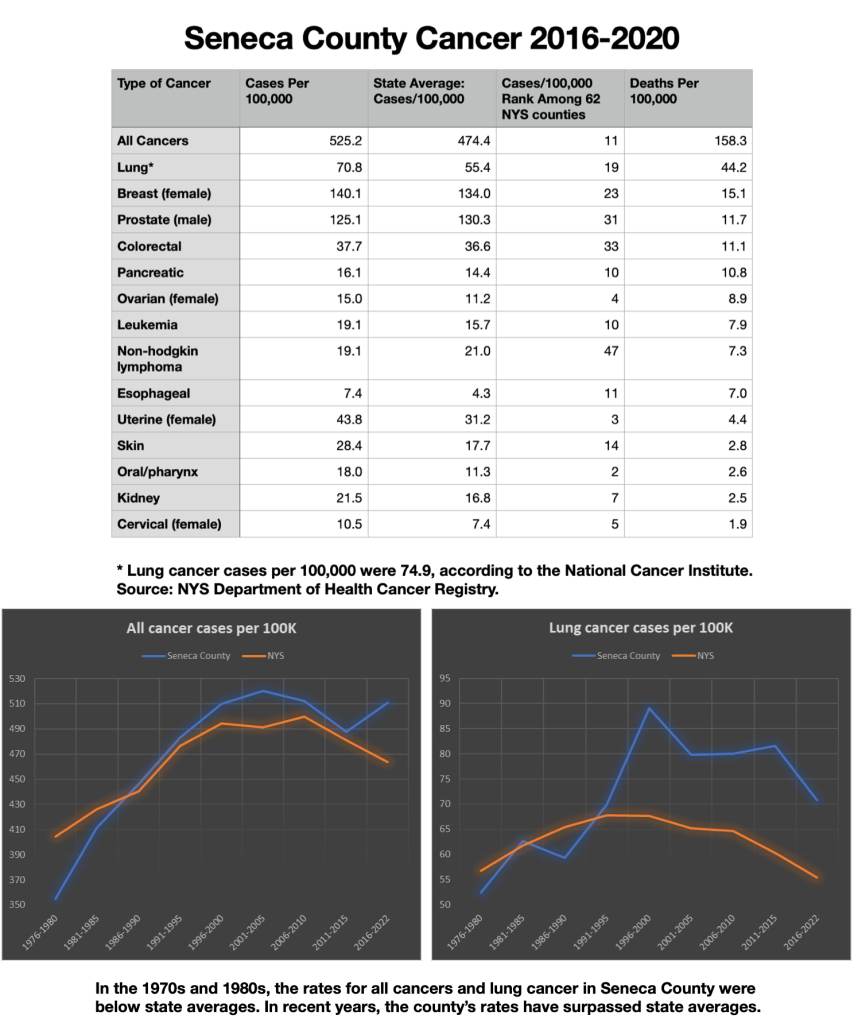

Over the next five years — 2016 to 2020 — lung cancer cases in Seneca County alone were 31 percent above the state average and 34 percent above the national average, according to the National Cancer Institute. County lung cancer death rates were 47 percent and 30 percent above the state and national averages, NCI reported.

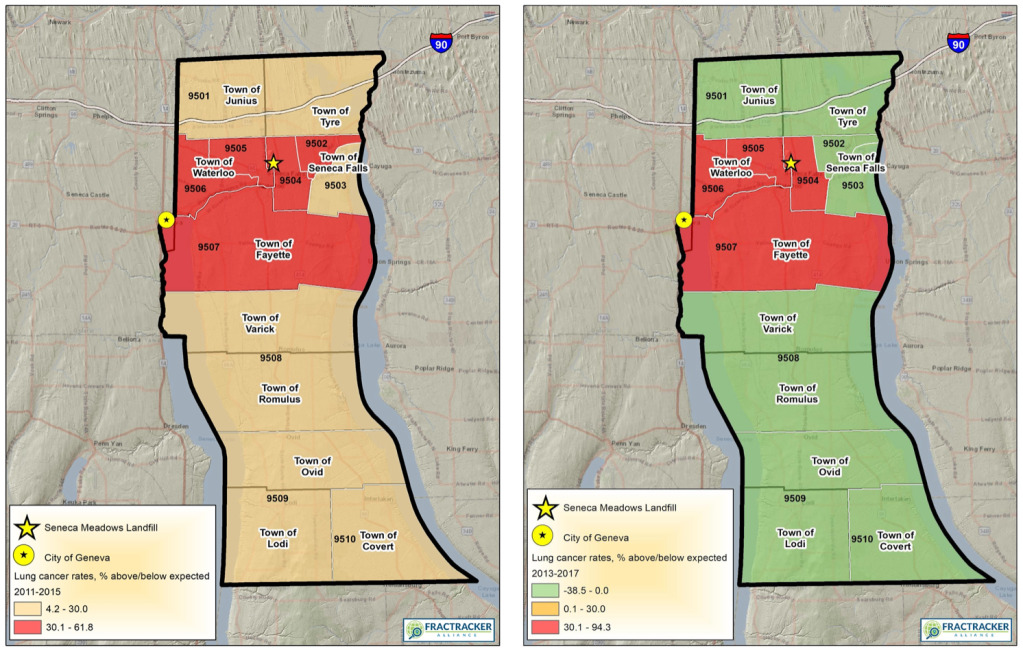

While lung cancer rates were moderate in the lower half of Seneca County, rates were particularly high across a band of census tracts that include Waterloo, Seneca Falls and Seneca Meadows Inc., the landfill that straddles the two towns, according to DOH stats for 2011 through 2017.

SMI is the state’s largest municipal waste landfill. It imports garbage from at least 40 New York counties, New York City, other New England states and Canada. Less 1 percent of its wastes come from Seneca County.

The landfill is seeking a state permit for a major expansion that would allow it to operate through 2040 at current dumping rates.

Environmental activists have been campaigning to force SMI to close by 2025. They’ve argued that the landfill’s pervasive noxious odors are a health hazard to children in particular, boosting asthma, headaches, burning eyes and the risk of cancer for people at nearby schools, homes and businesses.

While Seneca Meadows and an adjacent landfill gas-to-energy plant are the county’s runaway leaders in emitting gases that are known human carcinogens, it’s not scientifically sound to jump to the conclusion that their emissions are responsible for the higher lung cancer rates, health experts cautioned.

“There is no single thing that causes cancer of the lung,” said Dr. Earl Robinson, a pulmonologist in Elmira. “It’s a combination of genetics, toxin exposure, including smoking (the No. 1 cause of lung disease), radon (the No. 2 cause of lung cancer), asbestos, carcinogenic chemicals, etc.”

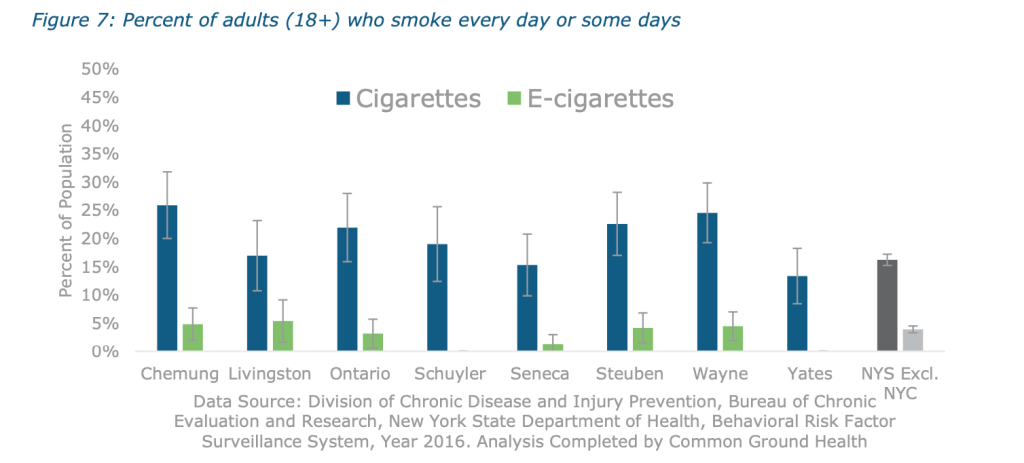

But smoking rates in Seneca County aren’t particularly elevated, and radon rates are well below the state average.

Could its lung cancer pattern be statistical fluke?

“There can be statistical differences that occur (in lung cancer cases) that aren’t related to any specific cause, like the landfill,” said Dr. David Carpenter, director of the Institute for Health and the Environment at the University of Albany, a branch of SUNY.

Lung Cancer by Census Tract

While the landfill’s gas emissions “suggest an association” with lung cancer, Carpenter added, proving the link would not be easy. And yet if the census tracts closest to the landfill have much higher rates than those further away, “that’s definitely telling,” he said.

Seneca Meadows and the energy plant fall in census tract 9504, a state-designated disadvantaged community. The DOH reported that lung cancer cases there were 36 percent higher than expected in 2011-2025 and 63 percent higher in 2013-2017.

During both periods (the latest five-year data published by DOH), the rates were at least 35 percent higher than expected in the census tract to the immediate south of tract 9504 and the two tracts to its west. The tract to the immediate east was 36 percent higher than expected in the first period before dropping sharply in the second.

In the three census tracts that cover the southern half of Seneca County, lung cancer rates were consistently closer to expectations over both five-year spans.

The DOH said Wednesday that it has stopped providing census tract data on cancer cases, based on guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Those entities had expressed “concerns of confidentiality and data stability for small numbers of cancers at census tract level,” DOH said.

The agency, which offers detailed data on its Cancer Registry website, said that “it’s typically difficult to attribute observed elevations of cancers to specific environmental causes.” Many factors can play a role in the development of cancer, DOH added, including “tobacco use, alcohol use, family history, radiation exposure, medical history, workplace exposures, infections, diet, sunlight, and physical activity,” among others.

Furthermore, “cultural factors associated with race, ethnicity and national origin, attitudes towards disease, interactions with health care providers and access to providers and adequate health coverage” are known to play important roles in cancer.

Read the DOH’s full response Wednesday to questions from WaterFront.

Smoking and Radon

Lung Cancer kills more people than any other cancer, statewide and nationally. But it has been in steady decline in recent years as rates of smoking have receded. Although the latency period for developing the disease can extend for decades, counties with current high rates of adult smoking tend to have the highest rates of lung cancer.

The DOH has estimated that 19.5 percent of adults in Seneca County smoke. That was higher than 43 counties, and lower than 18 counties.

But Common Ground Health, a Rochester-based research organization that focuses on nine Finger Lakes counties, pegged Seneca County’s adult smoking rate at around 15 percent, second lowest in the region and well below the state average.

After smoking, radon is the second leading cause of lung cancer nationally, killing an estimated 21,000 people a year.

In a DOH survey of radon levels on the first floor of homes in all 62 counties, Seneca County ranked in the bottom quartile. In fact, in almost half the counties, first-floor radon levels were at least as twice as high as Seneca County’s average level of 1.2 picocuries per liter.

In spite of Seneca County’s unremarkable smoking and radon levels, the county ranked 11th among 62 New York counties in rates of all types of cancer for the years 2016-2020, and 19th in cancer of the lung and bronchus.

Why do certain counties have higher cancer rates?

In 2017, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo launched a Cancer Research Initiative to study that question. Drawing on DOH data from 2011-2015, the project focused on Erie, Richmond, Warren and Suffolk counties.

The two downstate counties of Richmond (Staten Island) and Suffolk (eastern Long Island) had much lower lung cancer rates than Erie and Warren, as would be expected because the upstate counties had much higher smoking rates.

Of the four studied counties, Warren had the highest lung cancer rate — 79.3 per 100,000 people, which was significantly higher than the state average. DOH researchers primarily blamed smoking. They found no “unusual environmental exposures that could explain the elevated cancer indecent rates in Warren County.”

The University of Albany’s Carpenter sharply disagreed, and he wasn’t quiet about it.

Firing off a rebuttal to the DOH’s Warren County report, he said the state agency had failed to properly address the environmental causes of cancer, including particulate air pollution.

“The most blatant example of ignoring an environmental exposure known to cause cancer is the lack of any serious discussion of the possible role of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure, given the long history of exposure in this region,” wrote Carpenter, a renowned PCB expert.

He noted that PCBs were commonly dumped on Warren County roads and soils and that county residents tended to have high levels of PCBs in their blood.

“The great majority of the cancers that are elevated in Warren County are those that are known to result from PCB exposure,” he concluded.

Carpenter, who recently stirred controversy at the University of Albany over his PCB research, said the DOH “totally ignored” his Warren County rebuttal study.

PCBs are not known to be a problem in Seneca County, but the Seneca Meadows landfill and the adjacent landfill gas-to-energy facility release a host of toxic gases, according to 2017 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data. Several of those are classified as human carcinogens, including benzene, formaldehyde, vinyl chloride and trichloroethylene.

Hydrogen Sulfide, H2S or “Landfill Gas”

Another very common landfill emission, hydrogen sulfide (H2S), is not classified as a carcinogen, but it can cause nausea, headaches, burning of the eyes and coughing. Sometimes referred to as “landfill gas” or “sewer gas,” H2S is slightly heavier than air and accumulates in poorly ventilated or low-lying areas, including sewers and septic systems.

“Landfills are a common source of hydrogen sulfide which can particularly affect nearby communities,” the DOH website reports.

Scientists have used measurements of H2S as a surrogate for other carcinogenic gases that may be odorless. “If you have hydrogen sulfide coming off a landfill that you can smell, you can be damn sure it’s not the only chemical in the air,” Carpenter said.

Robinson, the Elmira pulmonologist, pointed to a massive, multi-year study of the health impacts of exposures to air emissions from nine Italian landfills near Rome. That study relied on hydrogen sulfide as an all-important “tracer” for other gas emissions.

Scientists tracked 242,409 people who lived within five miles of one of the nine landfills and reported their findings in a 2016 peer reviewed article published by the International Journal of Epidemiology.

The article revealed the “relatively new finding” that exposure to H2S was associated with lung cancer deaths. It also confirmed the previously established association between H2S and respiratory illnesses.

“H2S is produced by anaerobic decomposition of sulphur-containing organic matter in landfills,” the article stated. “(H2S) has been considered a surrogate measure of all contaminants emitted by landfills.”

The scientists estimated each subject’s degree of exposure to H2S and evaluated the health impacts on the subjects in each quartile of exposure.

“In conclusion, we found associations between H2S exposure from landfills and mortality from lung cancer as well as mortality and morbidity for respiratory diseases,” the scientists wrote. “The link with respiratory diseases has been observed in other studies and it is potentially related to irritant gases and other organic contaminants. The excess of lung cancer is a relatively new finding.”

The study noted links between H2S exposure and higher rates of hospital admissions for respiratory problems, especially in children.

The links discovered between H2S and respiratory illnesses and deaths in Italy were particularly noteworthy, the scientists said, in light of the noted absence of any association between H2S and cardiovascular disease.

Reaction to “Sewer Gas” Outbreak

Hydrogen sulfide is a hazardous volatile organic compound. Odors from it are part of everyday life in Waterloo and Seneca Falls.

It has been blamed for everything from driving school children off their playgrounds to triggering nasty hotel reviews to sabotaging corporate recruiting.

“The smell is breaking our brain cells,” one young student testified to the state Department of Environmental Conservation at a crowed public hearing in 2017. More than 20 other speakers told DEC officials the landfill odors were wrecking their quality of life and eroding their home values.

On some days, there is little or no odor. On others, it is so intense it is distracting.

“Currently, we have experienced a sewer gas odor so potent that some of our employees have felt sick and have been unable to work in the front offices,” Bill Lutz, president of Waterloo Container, wrote Scott King, director of the Seneca County Health Department, in May 2022. “This could not only be a health issue for our employees, but a liability for our company.”

That month, several other local businesses reported overpowering stench emanating from within their bathrooms and sinks. “It was so bad when I walked in this place, it took my breath away, gave me an instant headache,” said Randy Maestre, owner of Absolute Auto Repair on Route 414 in Waterloo.

To address the stench, Seneca Falls Town Supervisor Mike Ferrara ordered Seneca Meadows to stop discharging its leachate into the local sewer system “until we determine the cause of the excess hydrogen sulfide.”

After the landfill suspended its leachate flows, the indoor odors subsided.

A month after Lutz wrote his letter to King, the director of the county health department, King responded by explaining that experts at state Bureau of Toxic Substances Assessment said “there is a wide separation between hydrogen sulfide nuisance odors, which are offensive and perhaps nauseating, and the level of odors that are considered likely to impact health.”

Months passed.

On Oct. 11, 2022, Lutz wrote Dereth Glance, deputy commissioner of the DEC: “We asked the (county) health department to help us find answers,” Lutz wrote. “They told us to go to the DEC. We did, and here we are. Still in the dark.”

Lutz’s wife Annette had died of breast cancer in April 2019.

She had been diagnosed with the disease in 2011. Since 2005, she had worked in the Waterloo Container offices almost directly across the highway from the landfill and not far from the energy plant.

“Annette worked in the office and was exposed to the sewer gasses that had been coming into our building years ago when (the landfill was discharging) the raw form of leachate,” Lutz said. (All of Seneca Meadows’ current discharges into the town sewer system have been treated through a reverse osmosis process, but landfill officials have acknowledged that in the past they discharged untreated leachate.)

Over several years, as her disease progressed, Lutz said he and his wife consulted with cancer doctors at Roswell Park in Buffalo, Sloan Kettering in New York, as well as experts in Arizona and Israel.

“We did all the genetic testing,” Lutz said. “Every doctor said, ‘You’re not genetically prone to it.’ The only thing they could confirm was environmental.”

Annette Lutz began to suspect her workplace.

As a member of the Seneca Falls Town Board in 2016, she led the way to passage of Local Law 3, which required Seneca Meadows to stick to a firm closing data of Dec. 31, 2025.

Expanding the Landfill and the Energy Plant

That local law has roiled the community ever since. While many in the community complain about landfill odors, many others are enthusiastic supporters of the landfill and its continued operation.

Seneca Meadows sued to overturn Local Law 3, which had only partial support on the five-member town board. And in the closing days before the 2022 town board election, SMI’s Texas-based parent company, Waste Connections Inc., wrote a $200,000 check to support a group backing two town board candidates seen as opponents of the law. Those favored candidates ousted two supporters of the law, tilting the board majority in the landfill’s favor.

Earlier this month, state Supreme Court Justice Daniel Doyle ruled Local Law 3 invalid on the grounds that Lutz and the town board had failed to comply with rules of the State Environmental Quality Review Act (SEQRA) when they enacted it. His ruling is likely to be appealed.

Doyle’s decision removes a major roadblock to SMI’s bid for a DEC permit for a major expansion.

The so-called “Valley Infill” project would allow new waste to be piled on top of the 26-acre Tantalo Inactive Hazardous Waste Site on SMI’s property. The expansion would give the landfill space to continue operating until 2040 at current dumping rates.

The DEC has said it will require SMI to prepare an environmental impact statement, which under SEQRA will involve detailed analyses of environmental issues and public hearings.

The DEC said Wednesday it is preparing a final “scoping document” to define the issues that will be addressed in the environmental impact statement. The agency’s draft scoping document, issued in January, received about 600 comments during a 30-day public comment period. The DEC said there will be further opportunity for the public to comment later in the EIS process.

Kyle Black, district manager for Waste Connections and the top official at SMI, declined to respond to questions from WaterFront for this article.

“I would require more detailed information/facts on the data you are referencing to understand/comment,” Black said in a brief email. “SMI’s local highly skilled team of engineers, managers, technicians and operators maintain our facility in full compliance with all local, state, and federal regulations and permits.”

After being provided more detailed information, including the census tract maps, Black did not respond.

Meanwhile, the gas-to-energy plant owned and operated by Archaea Energy, is also seeking to expand. The Finger Lakes Times reported that the plant is a 17.6-megawatt facility that burns landfill gas from SMI. According to The Times, the plant operates 18 internal combustion engines that produce energy, as well as a BTU unit that recovers methane, refines it, and adds it to a local natural gas pipeline.

The company proposes to add a second, larger, BTU unit and convert eight of the 18 engines to burn natural gas rather than landfill methane.

The DEC has deferred to the Town of Seneca Falls to act as the lead regulatory agency in deciding how the state environmental law, SEQRA, will be applied in the plant’s application to expand.

The state agency confirmed Wednesday that no environmental impact statement will be required because “there is a negative declaration on file.” A so-called “neg dec” is a lead agency’s conclusion that a project will not have any significant impact on the environment.

The agency added: “DEC reviewed a permit renewal and modification application by Seneca Energy Landfill Gas to Energy (LFGTE) facility for its existing 17.6-megawatt landfill gas-to-energy facility. This application was public noticed and DEC is reviewing public comments. DEC is completing its technical review prior to making a decision on the proposal.”

Seneca Falls Town Supervisor Ferrara said in an email Tuesday he “100% agree(d)” that DOH data on lung cancer patterns should be included in debates about the permit applications from the landfill and the energy plant. He later added: “I am sure the EPA and DEC will review this data and will be part of their decision.”

Both facilities are located within a state-designated disadvantaged community. Both also fall within a census tract that had 23 lung cancer cases in 2016-2020, when the DOH calculated that only 14 were expected statistically.

According to 2017 data from the EPA, each of the two facilities emitted approximately 80 tons of volatile organic compounds (VOC) that year. All other county sources, including aircraft, emitted less than 10 tons of VOC in 2017.

Seneca Meadows emitted the most benzene (about 300 pounds) in 2017, followed by the energy plant (159 pounds).

The energy plant emitted more formaldehyde (nearly 70 tons), vinyl chloride and tricholoroethylene than the landfill. Combined emissions of those three human carcinogens from the two facilities dwarfed all other county sources, according to the 2017 EPA data.

I don’t know about “new” WaterFront blog. I’m about to begin the seventh year.

LikeLike

I hope the public can get a report of the last 5 years why are the latest report not available?

LikeLike

Good question for Gov. Hochul.

LikeLike

Department of Health claims they stopped tracking by census tract after 2017.

LikeLike