AURORA, Sept. 19, 2024 — In early June, 232 waterfront property owners and water users around Wells College Bay were mailed notices of a plan to apply herbicide along the east side of Cayuga Lake to eradicate the highly invasive plant hydrilla.

They were given 14 days to comment. Lack of response was considered consent to the planned chemical treatment and to restrictions on water use. Not one person expressed objections.

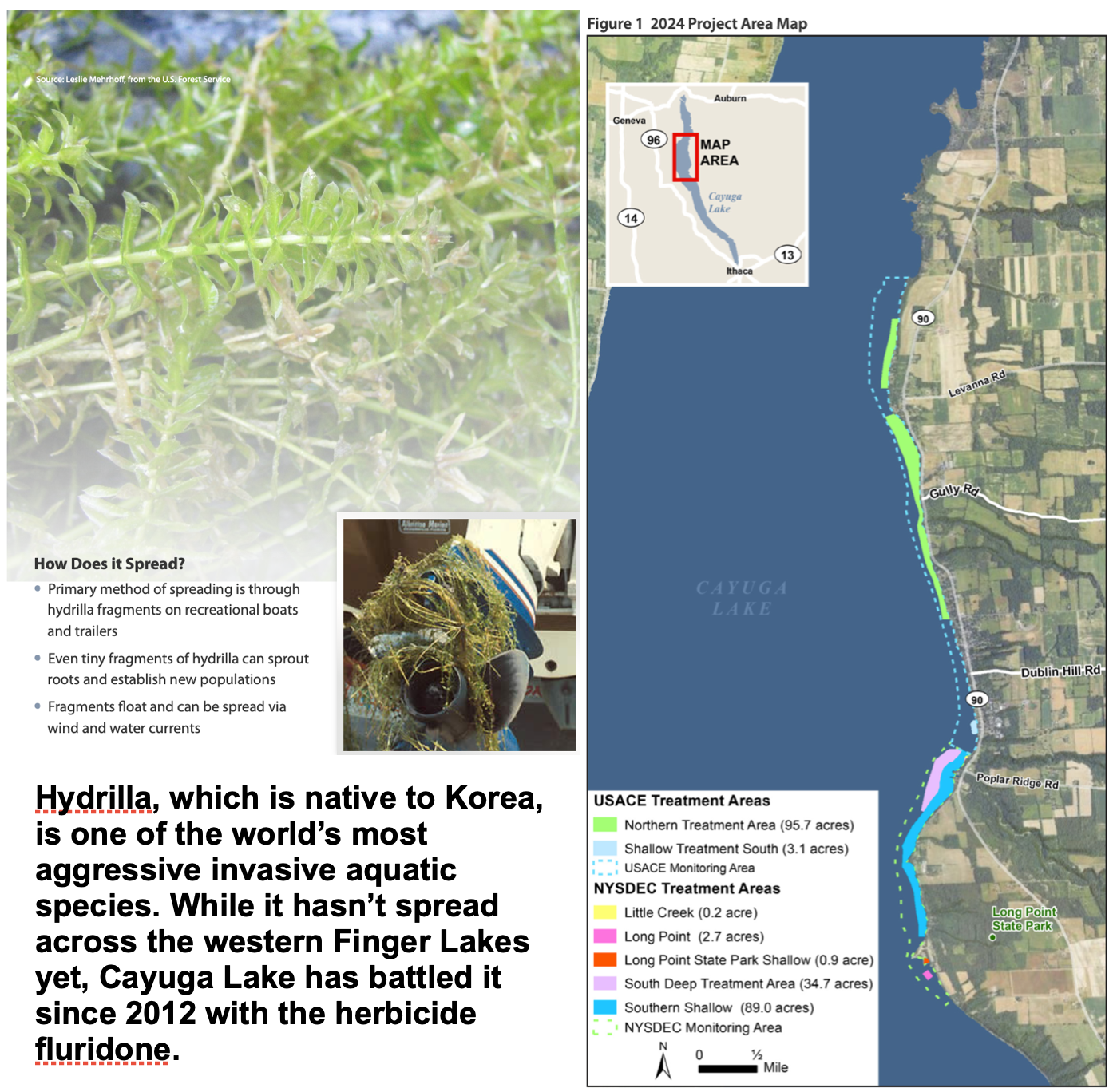

Between late June and mid-August the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the state Department of Environmental Conservation conducted a series of eight previously announced herbicide applications.

The agencies posted black and yellow signs to notify stakeholders of treatment areas around Aurora, warning them not to drink water if its herbicide levels exceeded the state’s limit of 50 parts per billion.

The project has had the support of local water quality experts, and it was carried out openly with a minimum of public commotion.

But in early September, in an opinion column a Cornell professor leveled a vigorous attack on the decade-long practice of applying the herbicide fluridone to various sectors of Cayuga Lake. Writing for Ithaca.com, Karan Mehta noted that fluridone has been associated with the class of harmful “forever chemicals” known as PFAS.

“Tens of tons of herbicide, including PFAS active ingredients, have been deliberately injected into Cayuga Lake over the last few years,” Mehta said. “A change of course is needed.”

Mehta, whose specialty is electrical and computer engineering, noted that herbicides have been used since 2012 in the Cayuga Outlet, a tributary south of the lake.

Until 2017 treatments were generally confined to the outlet and the lake’s southern end. More recently, the focus has shifted north.

This year contractors for USACE treated about 100 acres of near-shoreline areas north of Aurora, while contractors for the DEC treated about 130 acres immediately to the south.

Local water quality and invasive species experts generally support the initiative.

“Hydrilla is on the more extreme end of ‘invasiveness,’ and if left to spread naturally, it will change the ecology of both shallow ends and nearshore areas across (Cayuga Lake),” said Liz Kreitinger, executive director of the Cayuga Lake Watershed Network.

She also acknowledged the need to better understand the potential tradeoffs when relying on pesticides to manage hydrilla.

But Grascen Shidemantle, executive director of the non-profit Community Science Institute (CSI) in Ithaca, warned that “halting treatment altogether could erase years of progress” in eradicating hydrilla.

“It’s much easier to label a pesticide as the villain versus a plant, but this plant in particular can do a whole lot of damage to Cayuga Lake and surrounding lakes if left untreated,” Shidemantle added.

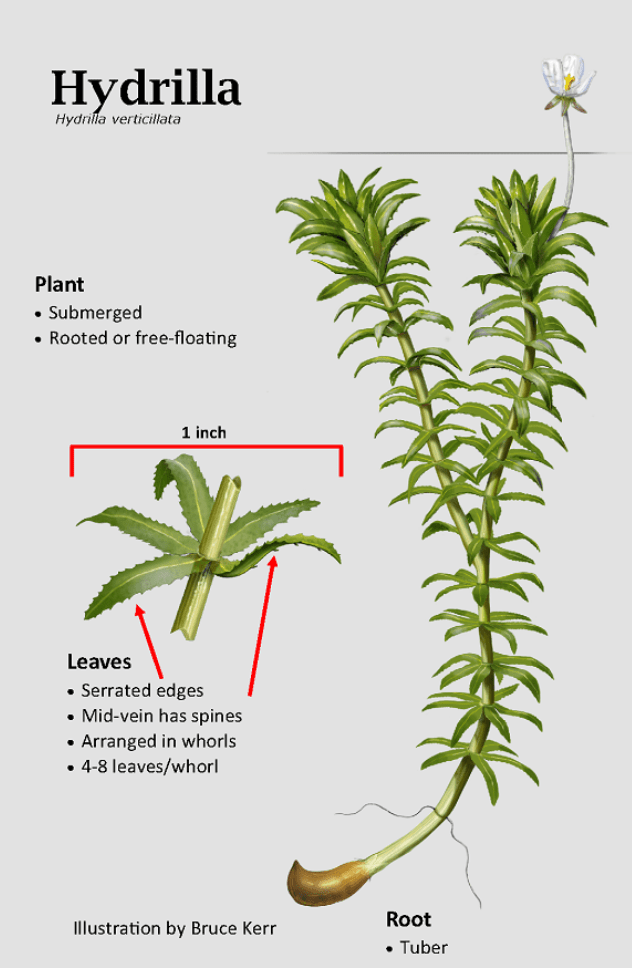

Native to Korea, hydrilla was first spotted in New York in 2008. From that first siting in a small pond in Orange County, it has spread to nearly a dozen other counties, the DEC reports. So far, hydrilla has largely spared Seneca Lake and other western Finger Lakes.

Plant fragments can be carried to new waterbodies by currents, boats, boat trailers or fishing gear. It spreads quickly, rooting in shallow water and rapidly growing up to 30 feet in length. Its stems branch at the surface of the water, forming dense mats.

In efforts to control its spread in Cayuga Lake, both USACE’s Buffalo Division and the DEC have supervised application the herbicides fluridone (trade name Sonar H4C) and chelated copper (trade name Harpoon Granular).

Hydrilla shoots absorb fluridone from the lake water, which “inhibits the formation of carotene, a plant pigment, causing the the rapid degradation of chlorophyll” that the plant needs to survive, the Cornell Cooperative Extension of Tompkins County (Tompkins CCE) reports.

One promotion touts fluridone’s effectiveness, claiming: “A multitude of pond professionals nationwide have ranked fluridone as a clear winner in the battle against duckweed, milfoil, watermeal and other problematic aquatic weeds that plague lakes, ponds, lagoons and irrigation canals year after year.”

But Mehta, the Cornell professor, notes that several states consider fluridone a PFAS chemical. PFAS (perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances) is shorthand for a class of thousands of highly toxic, man-made compounds that has come under increasingly strict regulation in recent years.

Exposure even to minuscule concentrations of PFAS — a few parts per trillion — can lead to liver damage, thyroid disease, obesity, fertility issues and cancer.

The states of Maine and Minnesota have included fluridone on their lists of active ingredients in pesticides that fit their definition of PFAS.

That definition — “a fluorinated organic chemical containing at least one fully fluorinated carbon atom” — is controversial. While 23 states, including New York, and several international agencies have adopted that language, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has not.

Last year the EPA announced that it would not have a single formal definition for PFAS, but would take a “case-by-case” approach, saferstates.org reports.

That EPA stance has come under fire from, among others, Dr. Linda Birnbaum, the former head of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

“This is not a new definition — it is a lack of definition, and it makes no sense,” Birnbaum said. “It is just going to lead to terrible confusion.”

Fluridone has been widely used as an herbicide for more than 40 years. In a 2016 report, Tompkins CCE cited various studies — many more than 20 years old — that dismiss potential human health effects if the product is used as instructed.

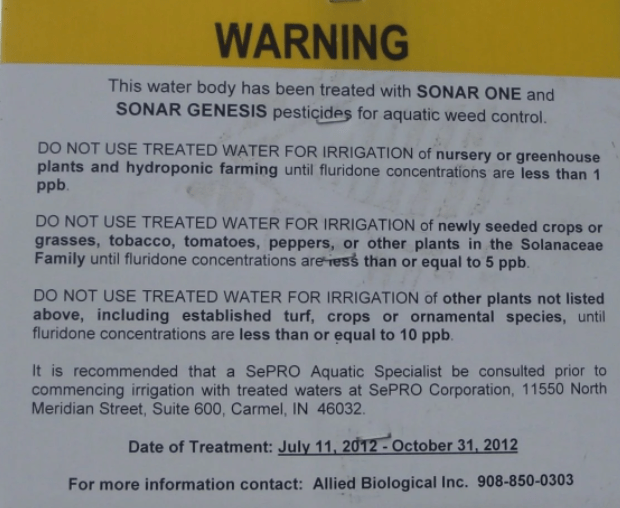

Fluridone is the active ingredient in Sonar H4C, which is manufactured by SePRO Corp. The company, which also makes Harpoon Granular, urges particular caution when irrigating with Cayuga Lake water treated with its herbicides.

The notification sent in June to Wells College Bay stakeholders notes that water found to have Sonar H4C concentrations greater than 1 part per billion should not be used to irrigate certain nursery and greenhouse plants. That compares to the much less restrictive 50 parts per billion limit for treated water that is said to be safe to drink.

The USACE’s 2024 hydrilla control project for the Well College Bay area included extensive water testing after the herbicide applications. The Cayuga County Health Department collects water samples that are analyzed by CSI in Ithaca.

The 2024 fluridone tests results for Aurora are available online.

Richard Ruby, a fish biologist with USACE-Buffalo, provided the data on the public notification letters and the lack of response.

Despite the efforts of USACE and the DEC to engage the public in their Cayuga Lake projects, Mehta expressed deep skepticism about their long-term commitment to using herbicides to control hydrilla.

“Over 30 tons of herbicide in five years, including PFAS active ingredients, right into the lake, deliberately, at a cost of millions. We seem to have little to show for this,” he wrote.

“… Would we have done better to allow hydrilla to grow, which in some cases and like many other aquatic grasses can in fact aid water quality?”

He concludes: “Humane, intelligent, and precautionary policies, as a major shift from recent practice, are needed to restore and improve the health of Cayuga Lake and surrounding areas.”

Kreitinger said the DEC has tried other methods of controlling hydrilla, including mechanical harvesting.

“It was not only unsuccessful but it can provide a major pathway for spread,” she said. “Hydrilla stems are brittle. Instead of being captured by the harvester, they break into small fragments and re-enter the water.”

What I find particularly alarming is the comparison between the one parts per billion for irrigation and the 50 ppb for drinking water? Did I miss read this? Where else are we doing this? there must be other instances and perhaps other methods that we haven’t explore because we’re not doing this in New York State?

LikeLike