ALBANY, Mar. 8, 2021 — Jittery over the state’s potential legal liability for contaminating private water wells with road salt, the state Legislature in February heavily revised its own December 2020 law that had called for a state task force to study road salt pollution.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo signed the original law Dec. 2 and the revised law Feb. 16. A potentially important legal precedent fell between those two dates.

On Dec. 9, a Rochester judge awarded more than $91,000 to a farmer and his wife who had claimed that road salt from the New York State Thruway contaminated a water well and ponds on their 191-acre farm in Phelps. The couple said pollution killed up to 80 of their cows and corroded their equipment.

While the dead cow claim wasn’t proven to “a reasonable degree of veterinary certainty,” John and Jan Frederick did prove a trespass, Court of Claims judge Renee Forgensi Minarik ruled in an order filed Dec. 30.

The NYS Thruway Authority’s “maintenance and use of rock salt” constituted “an unlawful invasion of their land” that raised sodium and chloride levels in the farm’s well water to the point that it was unfit for consumption, Minarik concluded.

She awarded the Fredericks the cost of switching to public water and for past and future monthly water bills, plus interest.

The state has not appealed.

“We do think it will be a good precedent on salt pollution,” said Alan Knauf, whose Rochester law partner Amy Kendall had argued the case at a five-day trial before Minarik 14 months ago.

“It may be the state didn’t want to go to the Appellate Division since if we won there it would have been a stronger precedent,” Knauf added.

New York has led the nation in spreading rock salt on state roads, but courts have generally declined to order payouts to those who have claimed to be damaged by the practice.

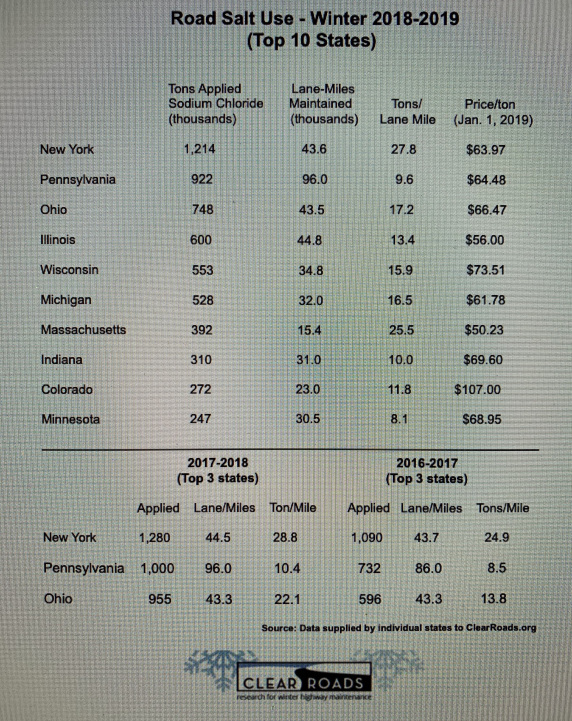

During the winter of 2018-19 and each of the two previous years, New York was the only state to spread more than 1 million tons of rock salt, or halite (chemical symbol NaCl), on its roadways, according to ClearRoads.org. It also led all states in rock salt spread per mile of state-maintained road — 27.8 tons per lane-mile in the 2018-19 season.

Salt spreading has been particularly heavy on state roads in Adirondack Park, a legacy of the decision to make road-clearing a top priority for the 1980 Olympic Games in Lake Placid.

Advocates led by the Adirondack Watershed Institute and AKDAction pressed state legislators to act.

The original law called for creation of a “salt reduction task force” to analyze the issue within the 6-million-acre park. The panel, which hasn’t been formed yet, would have officials from the state departments of transportation, health and environmental conservation, as well as independent scientists and local officials.

In January, Gov. Cuomo noted that the law focused on salt spreading by the state Department of Transportation but neglected salting of local roads, parking lots, driveways and sidewalks by local governments and private interests. The governor also said goals for reducing salt spreading should take into account the need to maintain safe roads for the driving public.

The revised law addressed Cuomo’s points. It also gave the DOT some control of the data it released to the task force and total control of releases to the public. Under the law signed last month, no information provided by the DOT to the task force may be released to the public “absent specific authorization” of the department.

And task force salt reduction recommendations must also include “estimated environmental, implementation and liability costs.”

The DOT has been sidestepping the liability question for decades.

Ry Rivard, a reporter with Adirondack Explorer, has documented several long-running legal battles involving property owners who blame road salt for poisoning their wells and ruining them financially.

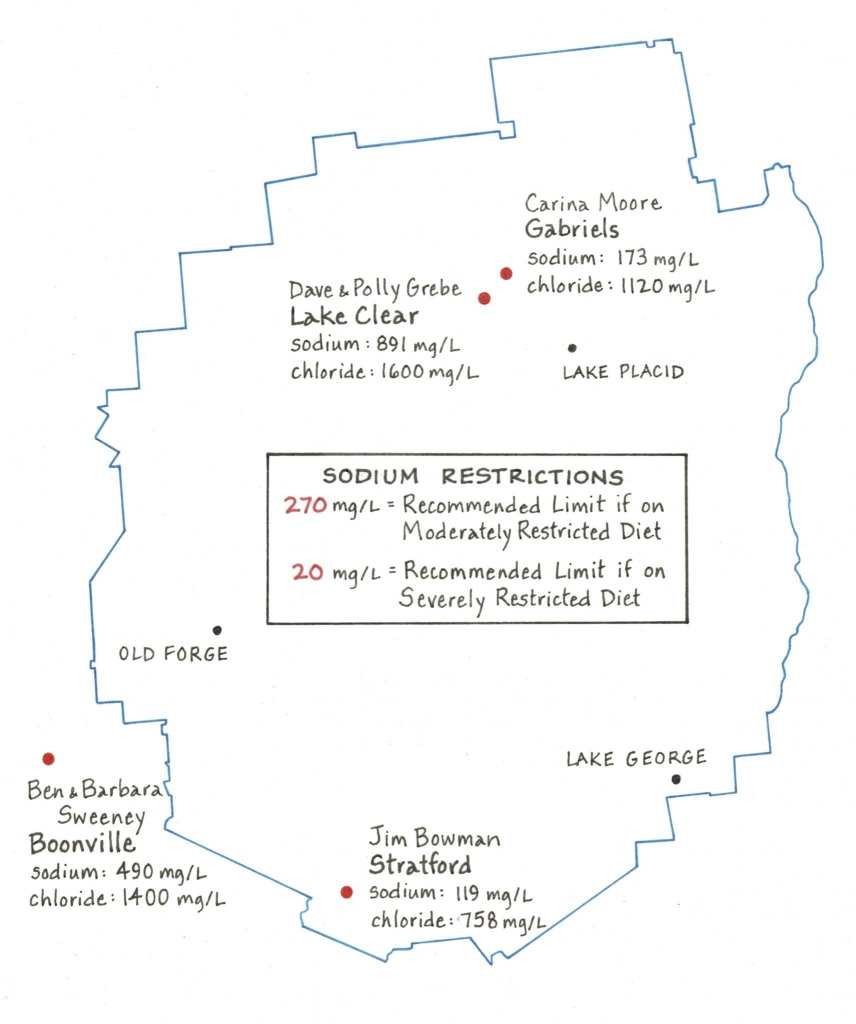

For example, Ben and Barbara Sweeney, who own a 300-acre dairy farm near Boonville, just southwest of Adirondack Park, began noticing troubling patterns with their cows in the 1990s.

In 2004, a state Department of Transportation official admitted in a letter that “it appears that your existing wells have been contaminated with road salt.” The Sweeneys say they have suffered a variety of personal health and financial problems since then.

The Sweeneys, like the Fredericks in Phelps, 110 miles to their west, claimed road salt in their ponds killed more than a dozen of their cows and reduced their herd’s milk production.

However, in the 2004 letter, the DOT official told Sweeneys that under the department’s current (2004) policy, “we can not pay for damages to private water supply wells resulting from routine road salting.”

In 2018, after years of legal skirmishing and after the farm had passed on to the next generation, the Sweeneys’ long-running legal battle was thrown out of court on a legal technicality.

The couple’s son, Brian Sweeney, who now owns the farm, told Rivard, “It’s a case they (the DOT) can’t afford to lose.”

Brittany Christenson, executive director of AKDAction, said households hit by road salt contamination often have nowhere to turn.

“Salt contaminated wells can be a costly crisis for families, and the contamination is almost always completely out of the control of the homeowner,” Christenson said in a recent email.

“I hope that the trespassing judgment (in favor of the Fredericks in Phelps) does open up some path for future remedy, as losing access to clean drinking water is a fate that no New Yorker should have to accept.”

The Adirondack Watershed Institute, an arm of Paul Smith’s College in Franklin County, and AdkAction were major drivers behind the push for a road salt reduction task force.

Dan Kelting, executive director of AWI, has estimated that the 2,830 lane-miles of state-maintained roads in Adirondack Park receive an average of 38 tons of salt per winter. After AWI tests several years ago showed elevated levels of sodium and chloride in many of the park’s lakes, AWI began testing about 500 private water wells in the park.

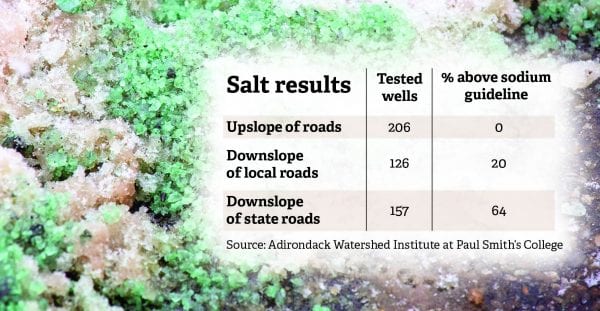

The data showed that salt contamination levels correlated to salt spreading on state roads. For example, all of the 206 wells upslope of park roads that were tested had sodium and chloride levels below federal health guidelines, while 64 of 157 wells downslope of state roads had readings above the health guidelines.

Kelting described the test well water with the highest sodium concentration as “way beyond undrinkable.”

He said he was optimistic about the prospects for addressing the issue through collaboration between the DOT, other state agencies and local officials.

State Sen. Timothy M. Kennedy (D-South Buffalo), chair of the Senate Transportation Committee, and Assembly Member Billy Jones (D-Plattsburgh) pushed for the original legislation to create the road salt task force and the revised law.

The DOT has described the revised law as “strong legislation that facilitates partnerships with local officials that can only help strengthen NYS DOT’s position as a national leader in the safe and balanced application of road salt in the North Country and across New York.”

Christenson of AdkAction credited the bills’ sponsors for engaging with supporters of the task force initiative. (AdkAction recently received a $50,000 grant to work towards reducing salt pollution along Lake Champlain.)

“The intent of the original law is retained, and the amendments are reasonable, especially in light of the state’s budget deficit and concerns about safety,” she added.

Peter,

Great article and good to know that NYS is beginning to pay attention. Thank you for your tireless research!

John

On Mon, Mar 8, 2021 at 8:04 AM Water Front- Peter Mantius wrote:

> Peter Mantius posted: ” ALBANY, Mar. 8, 2021 — Jittery over the state’s > potential legal liability for contaminating private water wells with road > salt, the state Legislature in February heavily revised its own December > 2020 law that had called for a state task force to study ro” >

LikeLike