CORNING, Mar. 30, 2020 — High levels of radon gas are “extremely likely” to be escaping from methane gas flares at the Hakes and Chemung County landfills, exposing landfill workers and nearby residents to dangerous levels of the carcinogen, health and science experts told a webinar audience Saturday.

To measure the extent of the near-certain health risks, they said, the state Department of Environmental Conservation must:

To measure the extent of the near-certain health risks, they said, the state Department of Environmental Conservation must:

— Begin continuous or frequent testing for radon in the methane flares.

— Begin building models of how the radon disburses, measuring its downwind concentrations.

— Resume the testing that agency officials allowed to lapse in mid-2018 for other radionuclides found in the landfills’ leachate.

“DEC is just basically denying that there’s this huge amount of (radon) release that (test) results show is extremely likely,” Dr. David Carpenter, director of the Institute for Health and the Environment at the University of Albany, told several dozen webinar listeners.

_________________________

“THE DEC IS JUST BASICALLY DENYING THAT THERE’S THIS HUGE AMOUNT OF (RADON) RELEASE THAT (TEST) RESULTS SHOW IS EXTREMELY LIKELY.”

— DR. DAVID CARPENTER

_________________________

“It is important to understand how much radium is in (Hakes) landfill, how much radon gas in being produced, and find ways to protect both workers and people who live around the site.”

The DEC declined to comment today, citing ongoing litigation. It said it works closely with the state Department of Health to ensure that the environment and public health are protected. The DOH did not respond today to emailed questions.

The latest calls for radon testing of Hakes’ methane flaring come from Carpenter and Raymond Vaughan, a geologist from Buffalo. Both have served as expert witnesses in legal action brought by the Sierra Club and others against the DEC over landfill permits.

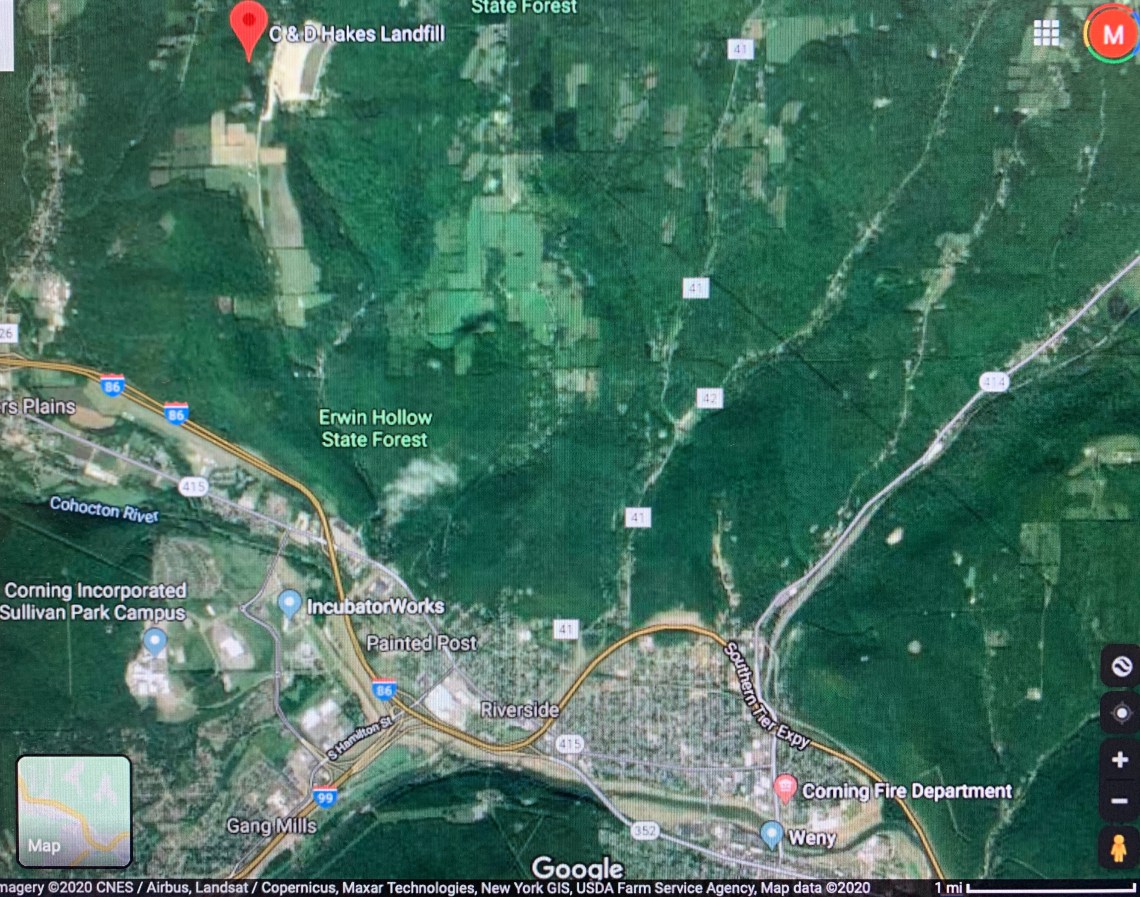

The DEC has long dismissed evidence that radioactivity exceeds safe levels at the Hakes Landfill six miles northwest of Corning or at the Chemung County Landfill seven miles east of Elmira.

The two landfills, both operated by Casella Waste Systems, have been the state’s two leading importers of drill cuttings from Marcellus Shale gas wells in Pennsylvania.

In December, when the DEC granted Casella, Hakes’ owner, a permit to expand, it effectively dismissed all assertions that the drilling waste has been contaminating the landfill with Radium 226 and its radionuclide progeny, including Radon 222.

Although Casella has reduced its drill cutting imports to Hakes, the agency hasn’t prohibited future imports. (Radon risks do not decline in proportion to the reduction of drilling waste imports because radon is constantly generated by whatever radium already exists in the landfill. Because Radium 226 has a half-life of 1600 years, its radon generation will have declined only slightly 100 years from today).

The DEC maintains that it has successfully enforced its Radium 226 limit of 25 pico curies/gram by requiring Casella to operate radiation detectors at landfill entrances.

But Vaughan doubts their reliability. “Waste truckloads can vary up to a factor of 60 in the radium levels while exhibiting the same or similar monitor readings at the gate,” he told the webinar audience. “It’s just not a test that discriminates properly.”

The webinar, which substituted for a scheduled public forum that was canceled due to the COVID-19 crisis, attracted about 70 listeners.

The event was sponsored by the Sierra Club, People for a Health Environment and Concerned Citizens of Allegany County. PHE has focused on radioactivity issues at the Chemung Landfill, while CCAC has concentrated on Casella’s Hyland Landfill in Angelica, the state’s third leading importer of Pennsylvania drilling wastes.

A decade-long citizens campaign to force the state to expand radiological monitoring at all landfills that accept drilling waste imports from Pennsylvania received a boost when Vaughan released his analysis of Hakes leachate in a lawsuit affidavit in early 2018.

Using results from 106 Hakes leachate tests obtained through the state’s Freedom of Information Law in late 2017, Vaughan discovered intermittently high levels of Lead-214 and Bismuth-214, which result from Radon 222 decay.

He concluded that radon gas mixed with the landfill’s emitted gas likely exceeds one million pico curies per liter (compared to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recommended action level of 4 pCi/L) either most or part of the time.

________________________________

“LANDFILL GAS IS CONSTANTLY BEING GENERATED (AT HAKES) THAT IS COLLECTED IN A PIPING SYSTEM SENT TO A FLARE….THE FLARE WILL DESTROY OR CONSUME THE METHANE, BUT IT WILL NOT AFFECT THE RADON.”

— RAYMOND VAUGHAN

_________________________________

After Vaughan filed an affidavit spelling out his findings in January 2018, the DEC allowed Casella to discontinue testing for the presence of the two tell-tale radionuclides, which are unmistakeable markers for Radon 222.

The DEC has claimed that the tests it once required were unreliable. Vaughan disagrees.

Carpenter, a former head of the state Department of Health’s Wadsworth Laboratory and a graduate of Harvard Medical School, found Vaughan’s analysis to be accurate and compelling.

In his own 2018 affidavit, he endorsed Vaughan’s conclusion that the landfill must contain extremely high levels of both Radium 226 and Radon 222, and he spelled out the implied health risks of radon gas emissions.

On Saturday he explained that radon, when inhaled, bombards lung tissue with heavy, DNA-altering alpha particles, often causing cancer. Radon is the nation’s second leading cause of lung cancer, after smoking.

“It directly damages DNA,” Carpenter said. “Mutation in the lungs is a major risk factor of lung cancer, which is much more dangerous to the young than the old and also to females than to males.”

Vaughan said the DEC has created a blind spot in its radiological testing by both neglecting to test for radon — by far the most dangerous nuclide in the entire uranium/radium decay chain — or radon markers such as Lead-214 and Bismuth-214. (Although his study has primarily focused on Hakes Landfill, he said results of leachate from Chemung County landfill also show Lead-214 and Bismuth-214 spikes.)

“We don’t know how much (radon) is escaping through the cap (landfill liners) and how much is being released from the landfill gas flare,” Vaughan said Saturday, elaborating on another affidavit filed this year.

“Landfill gas is constantly being generated (at Hakes) that is collected in a piping system sent to a flare,” he added. “A lot of the gas is methane, so it will burn. The flare will destroy or combust the methane, but it will not affect the radon.

“We don’t know how much radon is there, so testing is needed for that purpose.”

After this story was posted around 2 p.m. today, Casella regional supervisor Larry Shilling responded to questions emailed to him this morning. He said that other scientists not mentioned in this report do not believe proposed radon testing is warranted at Hakes.

In May 2018, Theodore E. Rahon, a health physicist with CoPhysics Corp., produced a report for Casella that sought to rebut Vaughan’s findings concerning the Hakes leachate test results.

Shilling concluded his email today by writing:

“Anyone concerned about this naturally occurring gas would have a far greater impact backing a campaign to pay for and install radon detection and mitigation in residential homes.”

For more on the DEC’s stance against radon testing at Hakes and against the resumption of tests for radionuclides in Hakes leachate, see previous WaterFront stories here and here.