WATKINS GLEN, Oct. 18, 2019 — Recent tests of public tap water in Watkins Glen, Montour Falls and Waterloo all confirmed traces of PFAS-class chemicals, but local officials said the measurements were well below levels the state Department of Health deems a risk to human health.

The three public water systems contracted for the latest tests in response to a drinking water survey Seneca Lake Guardian released to WaterFront in August, triggering public alarm.

The water systems’ test results from Microbac Laboratories Inc. all came in lower than the SLG findings, which themselves had fallen within the state’s proposed PFAS contamination limits.

PFAS chemicals are found in many common household products, including Teflon and Scotchgard. Even when present in only few parts per trillion in drinking water, they have been linked to serious health problems.

SLG had provided local water samples to a University of Michigan lab to screen for 14 PFAS chemicals in much the same way homeowners use radon kits to screen for radon in their basements. SLG reported a combined total of 21.0 parts per trillion for Watkins Glen, 17.6 ppt for Waterloo and 13.7 ppt for Montour Falls.

The Microbac test totals for the same 14 PFAS analytes was 2.51 ppt for Watkins Glen and 4.07 ppt for Waterloo. Montour Falls had yet not received a complete report from Microbac, but Mayor John King said that in one of the town’s two water wells only one of the 14 analytes had been detected. That reading was roughly 1 ppt, he said.

Watkins Glen Mayor Luke Leszyk said this week that the Microbac results “contradict” the WaterFront report on SLG’s initial findings.

“It is unfortunate that misinformation is put out with the appearance of fact and unnecessarily strikes fear in the public,” he wrote in a recent letter to The Odessa File, a local website. WaterFront stands by its reporting and notes that the SLG and Microbac tests are not strictly comparable.

The state DOH also took an indirect swipe at SLG’s survey.

“We work closely with communities and other stakeholders in these efforts every single day, and encourage people to contact us directly rather than relying on misleading data obtained by non-certified testing that serves only to confuse the public,” the agency said in a Sept. 18 statement to WaterFront.

But the DOH glossed over the fact that Microbac’s total PFAS results are no more valid than SLG’s results from the Michigan lab because the DOH has not certified Microbac to test for 12 of those 14 chemicals.

And the DOH appears to be overstating its willingness to communicate with “stakeholders” seeking PFAS data.

SLG has said it conducted its survey in response to the DOH’s unwillingness to supply requested PFAS data, particularly around the former Seneca Army Depot in Romulus.

Also, the DOH has not responded promptly to a WaterFront Freedom of Information Law request Sept. 3 for PFAS data that is readily available. On Oct. 2, the agency said it wouldn’t be responding before Dec. 4.

Furthermore, an independent test similar to SLG’s is widely credited with uncovering the state’s biggest PFAS scandal ever: Hoosick Falls.

Acting on his own, Michael Hickey obtained crucial PFAS data on Hoosick Falls drinking water after his father died of liver cancer attributed to the contamination. The DOH later confirmed his findings with its own followup testing.

That led the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to lower its national “advisory” limit for PFAS chemicals, and it prompted Gov. Andrew Cuomo to form a state Drinking Water Quality Council.

That council has proposed limits of 10 parts per trillion each for two PFAS chemicals — PFOA and PFOS. The DOH said it plans to enforce those limits sometime next year. (If and when it does, the limits will be among the strictest in the nation. The EPA advisory limit of 70 ppt is not enforceable.)

The DOH plans to skip measurement or enforcement of 12 of the 14 PFAS analytes that SLG screened for.

Why did SLG chose that list of 14? The group is a nearly identical match to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s list of 14 PFAS chemicals most commonly found in the blood serum of tens of millions of Americans.

The National Resources Defense Council and several New York groups now argue that the pending state limits don’t go nearly far enough.

“Based on all available science, we do not believe regulating just two PFAS chemicals in New York goes far enough, when the dangers of the larger class of these chemicals is quite clear,” Environmental Advocates of New York said in a Sept. 23 letter to DOH Commissioner Howard Zucker.

The letter is signed by representatives of Seneca Lake Guardian, Food & Water Watch, New York Public Interest Research Group and others.

The environmental groups argue that the state should set a limit of 2 parts per trillion for any combination of these four chemicals:

— PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic acid).

— PFOS (Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid).

— PFNA (Perfluorononanoic acid).

— PFHxS (Perfluorohexanesulphonic acid).

Based on Microbac test results, Watkins Glen would meet that standard after showing 1.46 ppt for PFOA and non-detections for the other three. Waterloo wouldn’t comply because its PFOA of 1.24 ppt and PFHxS of 2.83 ppt total 4.07 ppt.

Jim Bromka, manager of the Waterloo water system, said PFAS contamination wasn’t his primary concern at the moment, given the fact that his plant will easily comply with state regulations next year and he’s eyeing a new $2.5 million filtering system.

“What’s definitely in front of our faces right now is HABs (harmful algal blooms),” Bromka said. “You’ve got the microcystins that are visible. The lake is green.

“You run the tests and it comes out as a HABs, so you don’t want to be drinking the water.”

In contrast to HABs, Bromka described the PFAS threat as “something brand new on the horizon.”

He acknowledged that testing for PFAS at his plant might yield entirely different results from tests at a home or business that draws water from that plant.

“I’m wondering if people have plumbing in their home and plumbers had at one time used a teflon tape, some of that stays in the water as it goes past it,” he said.

Mary Anne Kowalski, SLG’s research director and a former senior official at the DOH, agreed saying, “It’s good that (PFAS) is not in the public water supply at problematic levels, but it could still be in your home.”

SLG collected its Watkins Glen sample from a rest room at a local business. Its Montour Falls sample came from the county administration building. The Waterloo system sample came from a private home near the former Seneca Army Depot, where the use of fire-fighting foam caused PFAS contamination to spike.

SLG had chosen to test the Waterloo system because of its proximity to the depot, where extraordinarily high PFAS readings — up to 92,000 ppt — had been reported by a contractor for the U.S. Army.

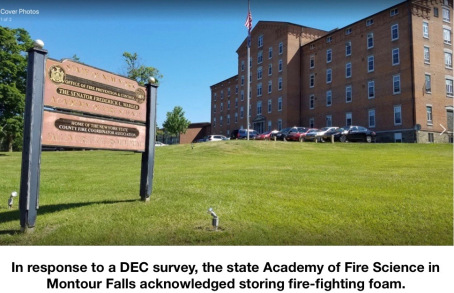

It chose Montour Falls because state officials had identified the New York State Fire Academy as a possible source of PFAS because it had stored and/or used fire-fighting foams laced with PFAS chemicals. Watkins Glen was chosen because of its proximity to Montour Falls.

In each case, SGL officials said they followed the instructions of the Michigan lab in obtaining and delivering the water samples.

Microbac required even more rigorous standards for obtaining and delivering water samples from local water department officials.

Microbac is based in Pittsburgh and operates in more than a dozen states.

Records show that the Pennsylvania Department of Environment Protection has cited the company for various violations of water analysis procedures.

For example, in 2013 the company entered into a consent agreement with the Pennsylvania DEP over alleged violations at its Baltimore Division.

The following year the DEP assessed a $220,000 fine for violations at Microbac’s Erie Division.

Microbac did not return phone calls or emails seeking comment.